Brave and beautiful: Longborough’s Pelléas et Mélisande reviewed

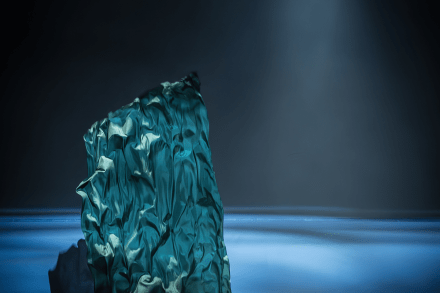

King Arkel, in Debussy’s Pelléas et Mélisande, is almost blind, and he rules over a kingdom of darkness. Debussy’s score is so luminous that it’s easy to forget just how dark it supposedly is, this mythical realm of Allemonde – even despite the libretto’s references to gloomy caves, shadowy castles and forests that block out the sunlight. Many productions take their visual cues from the music rather than the words, providing endless opportunity for shimmering effects and the subtle play of light and shade. Jenny Ogilvie’s staging for Longborough Festival Opera doesn’t just embrace the darkness; it goes all in. Shadows texture the huge, brutalist wall of Arkel’s castle and