The Spectator’s Notes | 23 November 2017

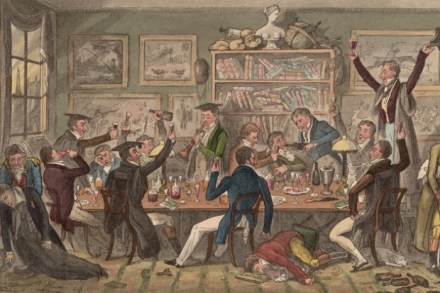

Windsor Castle on Monday night sounds like a children’s party magnified. The rooms were filled with golden-leaved trees. A giant block of ice carved with the initials of the Queen on one side and the Duke of Edinburgh on the other dominated the reception room. Her sons wore their Windsor coats. A magician made a table levitate and move unsupported round the room. As with a children’s party, there were no speeches, and everyone was pleased and excited. After 70 years married, the two nonagenarians involved presumably felt, among family and friends, that they had earned the right to be unserious. The occasion must have been sweet for Prince Philip.