Cricket’s dilemma

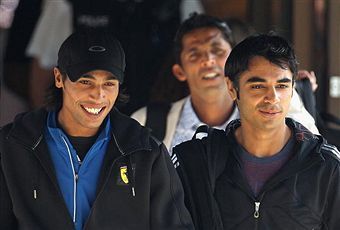

That the three Pakistani cricketers involved in the spot-fixing allegations have withdrawn from the rest of the tour means that the T20s and one day games will now definitely go ahead. If the accused had played, it would have been hard to see how the matches could have gone ahead and if they had, how they could have been taken at face-value by anyone. If the allegations against the men turn out to be correct, then the game will have to decide how to punish them. This is going to be a hard call. On the one hand, banning them for life would serve as a real deterrent to anyone