Are Mozart’s forgotten contemporaries worth reviving?

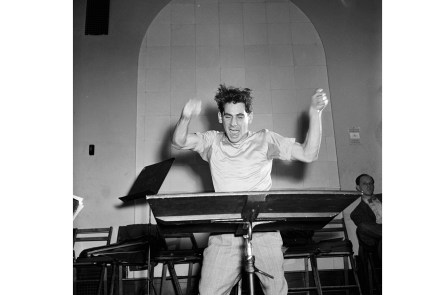

There are worse fates than posthumous obscurity. When Mozart visited Munich in October 1777, he was initially reluctant to visit his friend, the Bohemian composer Josef Myslivecek. Myslivecek was in hospital, undergoing treatment (as he told it) for a facial cancer brought on by a recent coach accident. But this being the 18th century, and Myslivecek having a reputation as a gallant, Mozart suspected venereal disease. When he finally appeared at Myslivecek’s bedside, he was appalled by what he saw: ‘The surgeon, that ass, has burned off his nose! Imagine the agony he must have suffered.’ Within four years, the luckless — and noseless — Myslivecek had died in poverty,