A philosophical quest: A Fictional Inquiry, by Daniele del Giudice, reviewed

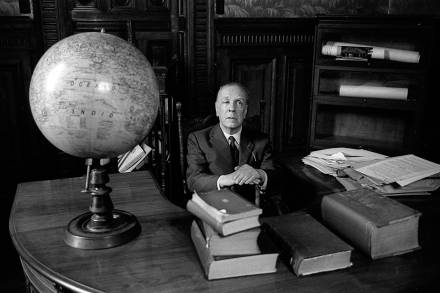

A researcher arrives in Trieste to piece together the life of a well-known literary figure. In cafés, bookshops and hospitals he visits the friends and lovers who were part of the writer’s circle. Now dying themselves, they share echoes of a literary scene that has long since dispersed. Women recall how they were celebrated in poetry; men how their conversation sparkled. Someone remembers how the writer once asked if he might immortalise one of his witticisms in his work: ‘Forty years ago I made a joke in a bar, and he said “Oh that’s good! Will you give it to me? I want to put it in my novel.’” But