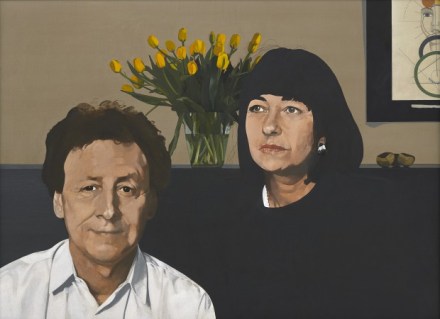

In a class of their own

Painters and sculptors are highly averse to being labelled. So much so that it seems fairly certain that, if asked, Michelangelo would have indignantly repudiated the suggestion that he belonged to something called ‘the Renaissance’. Peter Blake is among the few I’ve met who owns up to being a member of a movement; he openly admits to being a pop artist. The odd thing about that candid declaration is that I’m not sure he really is one. A delightful exhibition at the Waddington Custot Gallery presents Blake in several guises, including photorealist and fantasist, but — although one of the exhibits is an elaborate shrine in honour of Elvis Presley