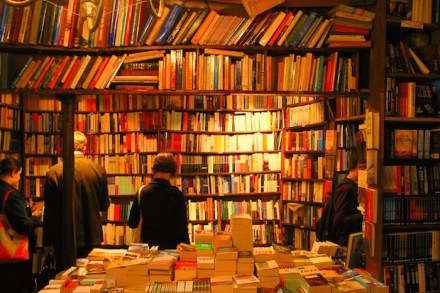

The pleasures of reading aloud | 24 August 2017

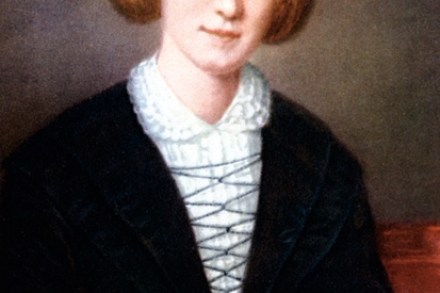

‘I have nothing to doe but work and read my Eyes out,’ complained Anne Vernon in 1734, writing from her country residence in Oxfordshire to a friend in London. She and her circle of correspondents (who included Mary Delany, the artist and bluestocking) swapped rhyming jokes, ‘a Dictionary of hard words’, and notes on what they were currently reading. Their letters are suggestive of the boredom suffered by women of a certain class, constrained by social respectability and suffering the restlessness of busy but unfulfilled minds. But that’s not their interest for Abigail Williams in this fascinating study of habits of reading in the Georgian period. Her quest is rather