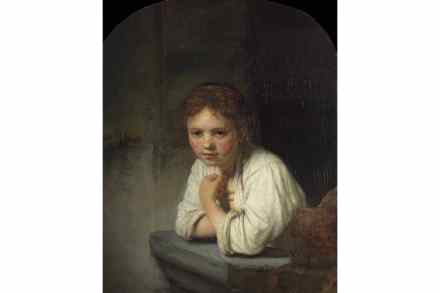

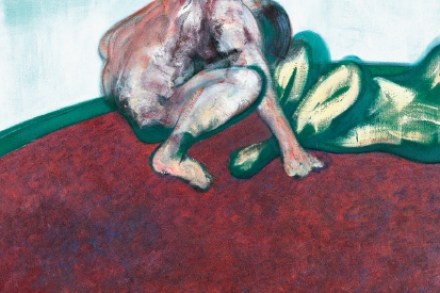

Whipping up a masterpiece: painters and their materials

If you are someone who revels in the deliciousness of oil paintings, who looks at them and wants to eat them ‘as if they were ice cream or something’, in Damien Hirst’s phrase, then Martin Gayford’s latest book will be a banquet. In part, this is thanks to the illustrations – luscious close-ups of Van Gogh’s brushstrokes like buttercream icing, and a double-page spread of a golden Rothko large enough to tumble into. But mainly it’s due to his intention to understand the medium of painting from the inside out: from the artists’ viewpoint rather than the art historian’s. He is well placed to do this, having interviewed almost every