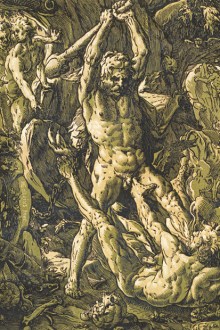

Is this the greatest sculpted version of the Easter story? It’s certainly the strangest

In April 1501, about the time Michelangelo was returning from Rome to Florence to compete for the commission to carve a giant marble David, a very different sculptor named Tilman Riemenschneider agreed to make an altarpiece in the small German town of Rothenburg ob der Tauber. Since then, things have not changed much in Rothenburg. Though battered during the war, it has been restored to postcard perfection (or rather turned into a perfect place for tourists to take selfies of themselves against a Disneyesque medieval background). And the Altar of the Holy Blood is still there, in the place for which it was made, at the west end of the