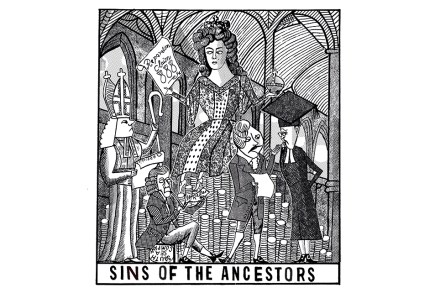

Should Britain pay reparations to Commonwealth countries?

16 min listen

This week, Keir Starmer has been in Samoa for a summit with delegations of the 56 nations which make up the Commonwealth. Between having to answer questions on Donald Trump and the budget, he has also been pressed on the issue of slavery reparations, with the leaders of some Caribbean countries insisting it is ‘only a matter of time’ until Britain bows to demands of handing over billions of pounds in compensation. Speaking today, Starmer addressed the issue. He said, ‘I understand the strength of feeling’ but insisted that he would be ‘looking forward, not back’. So what are the arguments for and against reparations? And why is this debate