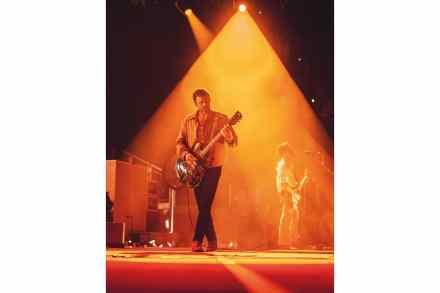

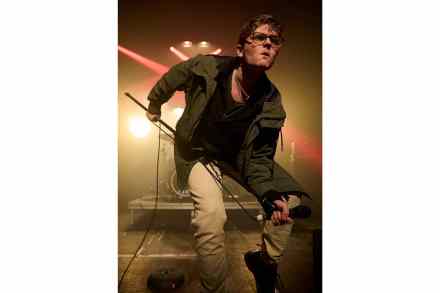

Only traces of their eerie early spirit remain: Kings of Leon, at OVO Hydro, reviewed

A few years ago, I spoke to Mick Jagger and asked him which of the (relatively) new crop of rock groups he rated. It was a short list, I recall, and not hugely inspiring, but Kings of Leon made the cut. ‘They have a kind of Texas weirdness that you don’t find in a lot of modern rock bands,’ he reckoned. ‘I like their quirkiness, and the fact that you can hear the countryish and blues thing behind them, but it’s not that obvious.’ Aside from the fact that they are from Tennessee, not Texas, it felt like a reasonably astute summation of Kings of Leon’s appeal when they first