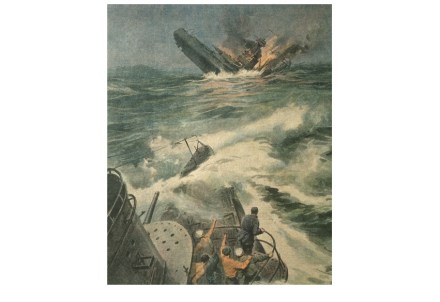

The Spectator at war: Revenge on the seas

From News of the Week, The Spectator, 12 December 1914: The week has been a week of good news. Last in order but first in importance comes the naval victory off the Falkland Islands. No summary of this news can better the Admiralty’s own report, which is splendid in its terseness and reticence:— “At 7.30 a.m. on December 8th, the Scharnhorst,‘Gneisenau,’ ‘Nürnberg,’ ‘Leipzig,‘ and ‘Dresden’ were sighted near the Falkland Islands by a British Squadron under Vice-Admiral Sir Frederick Sturdee. An action followed, in the course of which the ‘Scharnhorst,’ flying the flag of Admiral Graf von Spee, the ‘Gneisenau,’ and the ‘Leipzig’ were sunk. The ‘Dresden’ and the `Nurnberg’