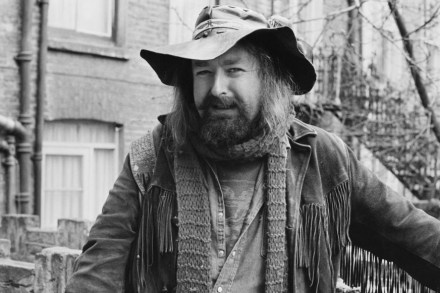

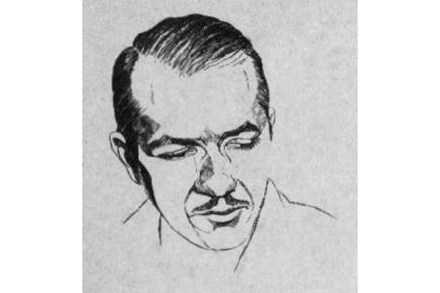

The young Anton Chekhov searches for his voice

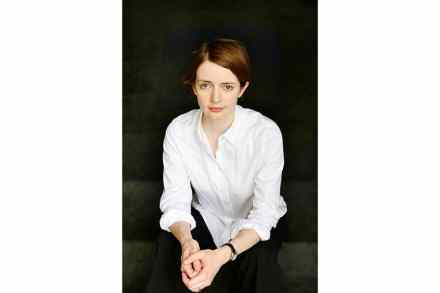

This book collects 58 pieces of fiction that Anton Chekhov published between the ages of 20 and 22. Many appear in English for the first time. In her introduction, Rosamund Bartlett refers to the material with disarming candour as a ‘wholly unremarkable debut’. Is there ever any point in publishing juvenilia? In his first years as a medical student Anton Pavlovich dashed off these pieces for a few kopecks a line (his father, born a serf, was a bankrupt shopkeeper). Ranging in length from three paragraphs to 76 pages, they appeared under pseudonyms in lowbrow comic magazines that included another Spectator (founded in Moscow in 1881). Unremarkable they may be