Deborah Ross: 12 Years a Slave harrowed me to within an inch of my life

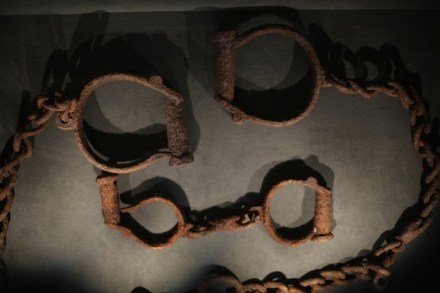

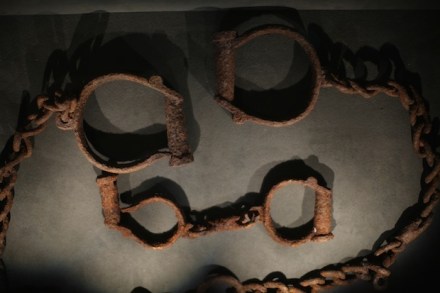

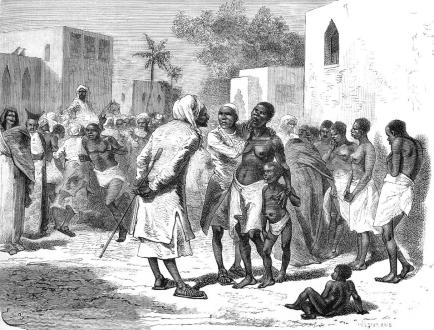

Steve McQueen’s 12 Years a Slave goes directly to the heart of American slavery without any shilly-shallying — unlike The Butler, say, or even Django Unchained — and is what I call a ‘Brace Yourself’ film, as you must brace yourself for horror after horror, injustice after injustice, shackles, muzzles, whippings, rapes, hangings. You will be harrowed to within an inch of your life, as perhaps is only right, given the subject matter, but you will not wish to flee your seat. You will recoil. You will flinch. You will say to yourself, ‘Oh no, not again.’ But the story will seize you with such a visceral power you will