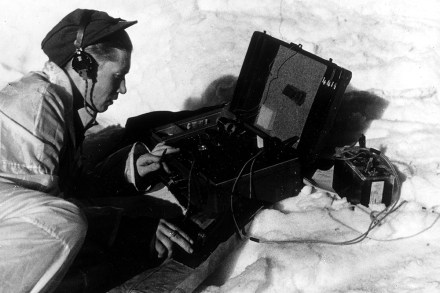

Heroes of the Norwegian resistance

Reading Robert Ferguson’s fascinating history of the experiences of the Norwegians during the five years of German occupation between 1940 and 1945 – a collage of resistance, collaboration and the grey areas in between – I was reminded of the remarks of two Norwegian nonagenarians. In 2011, I interviewed Gunnar Sonsteby, a hero of Norway’s resistance movement, for The Spectator. The country’s most decorated man, Sonsteby told me that he was spurred to acts of sabotage and the ‘liquidation’ of collaborators by sheer outrage at the German presence. Conversely, earlier this year, I wrote the obituary of Olav Thon, the owner of a chain of supermarkets and hotels and one