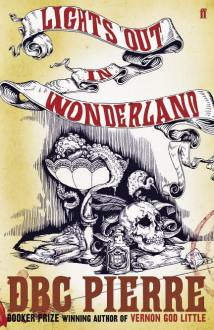

Madness and massacre in the jungle

In his new novel, Children of Paradise, Fred D’Aguiar, a British-Guyanese writer, returns to the Jonestown massacre, previously the subject of his 1998 narrative poem, ‘Bill of Rights’. D’Aguiar often examines brutal historical episodes from the perspective of a survivor or escapee. In Feeding the Ghosts (1997), the drowning of 140 slaves in 1798 so that the Liverpool-based owners could claim on the insurance is told through the story of Mintah, the one slave who did not die. In the new novel we have Joyce and her daughter, Trina, Americans who, having fallen for the messianic allure of ‘the preacher’ (a figure based on Jim Jones) and followed him to