Guilt-free hilarity: Vanya and Sonia and Masha and Spike at Charing Cross Theatre reviewed

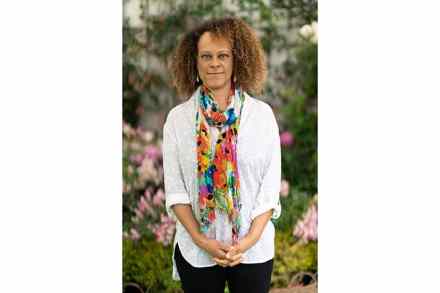

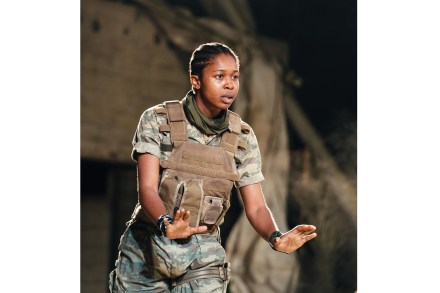

World-class sex bomb Janie Dee stars in a fabulously silly revival of the American comedy Vanya and Sonia and Masha and Spike. She plays a movie diva, Masha, who loves to flaunt her wealth in front of her mousy sister and bookish brother. Striding into the family home with her long hair flying and her scarlet lips curling, she narrows her eyes and flings shafts of desire in all directions. Then she arches her neck and tosses back her head to give her bust an extra half-inch of uplift. A stunning display. The show is about three middle-aged siblings whose over-intellectual parents named them after characters in Chekhov plays. Vanya