Nice work

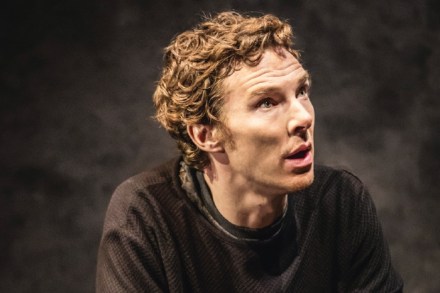

[audioplayer src=”http://rss.acast.com/viewfrom22/merkelstragicmistake/media.mp3″ title=”Kate Maltby and Igor Toronyi-Lalic discuss Benedict Cumberbatch’s Hamlet” startat=1642] Listen [/audioplayer]You can’t play the part of Hamlet, only parts of Hamlet. And the bits Benedict Cumberbatch offers us are of the highest calibre. He delivers the soliloquies with a meticulous and absorbing clarity like a lawyer in the robing room mastering a brief before his summing-up. And though he’s a decade too old to play the prince (the grave scene sets his age at about 28), he cavorts about the stage like a ballet dancer delighting in his own athleticism. But he’s also much too nice. The darkest shades of melancholy and the raw emotional ugliness are