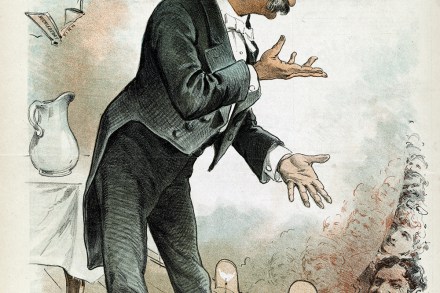

What Mark Twain owed to Charles Dickens

You know Mark Twain’s story. You’ve got no excuse not to; there have been so many biographies. Starting in the American South as Samuel Clemens, he took his pen name from the call of the Mississippi boatmen on reaching two fathoms. His lectures, followed by his travel pieces and novels, enchanted America and then the world. As a southerner, his principled stance against slavery gave him moral authority. The famous ‘Notice’ to The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn – ‘Persons attempting to find a motive in this narrative will be prosecuted; persons attempting to find a moral in it will be banished’ – was swept aside, so that persons like H.L.