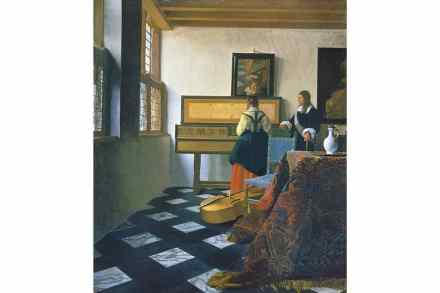

The golden age of Dutch art never ceases to amaze

This year’s Vermeer exhibition at the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam and the Frans Hals retrospective at London’s National Gallery are testaments to the enduring appeal of the Dutch artists of the Golden Age. When the 80-year war between Spain and the Dutch Republic ended in 1648, it left the Dutch strong in military and economic terms. They founded colonies across the world. The affluence and stability provided the perfect medium for creativity. Painting flourished, and buying art was no longer the domain of the wealthiest. Benjamin Moser’s first book since winning the Pulitzer for Sontag explores this burgeoning world. The lives and works of the greatest and lesser-known Dutch artists of