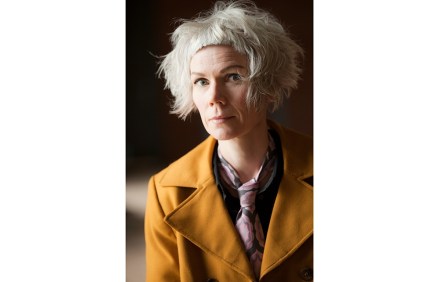

Bittersweet memories: Ti Amo, by Hanne Ørstavik, reviewed

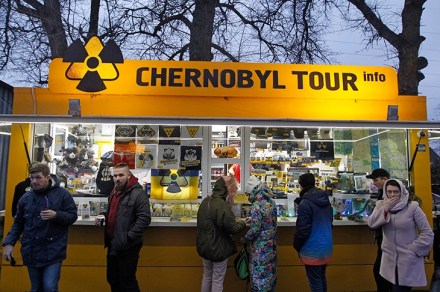

This is a deceptively slim novel. Its 96 pages contain multitudes: two lives, past and present, seamlessly interwoven. The narrator, a Norwegian novelist, and her Italian husband live in Milan. ‘Ti amo,’ they frequently tell each other. Easier to say ‘I love you’, than for him to say he’s dying, and her to say she doesn’t know what she’ll do without him. When did it all start, she wonders. ‘When did you actually become ill?’ We’re encouraged these days to view everything as a journey, including marriage, and theirs has been a marriage of many journeys, emotional and geographical: literary festivals, seminars, conferences, interspersed with private time – dinners in