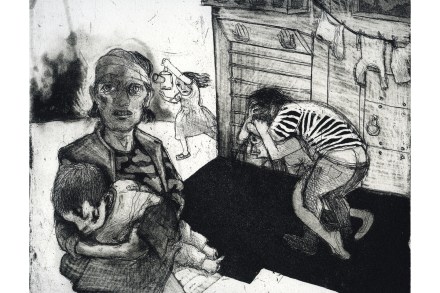

Why is the smoky, febrile art of Marcelle Hanselaar so little known?

I first became aware of the work of Marcelle Hanselaar in a mixed exhibition at the Millinery Works in Islington. All I remember now about the show, and my review, is that I said she could teach Paula Rego to suck eggs. From the mischievous energy packed into her small figurative paintings I assumed she was young enough to be Rego’s granddaughter. That was in 2003; she was pushing 60. Born in Rotterdam in 1945, Hanselaar is essentially self-taught. She dropped out of art school in The Hague — it was the 1960s — and ran away to Amsterdam; what she learned about painting she picked up from the artists