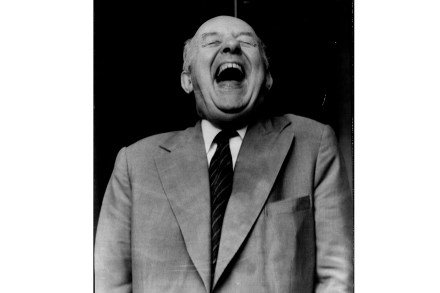

Richard Ellmann: the man and his masks

Richard Ellmann’s acclaimed life of James Joyce was published in 1959, with a revised and expanded edition appearing in 1982. The first edition, the work of an ambitious young American academic, received what Ellmann’s editor at Oxford University Press described as ‘the most ecstatic reaction I have seen to any book I have known anything about’. Ellmann’s work would ‘fix Joyce’s image for a generation’ wrote Frank Kermode in The Spectator, a prediction described by Zachary Leader as ‘if anything, too cautious’. By the time of the second edition, Ellmann had become a lionised Oxford don and the image of Joyce he had fixed was starting to chafe. Post-structuralism was