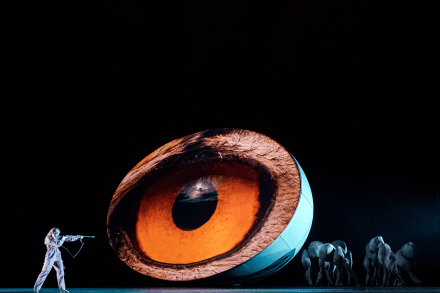

A spectacular failure: Royal Ballet’s MaddAddam reviewed

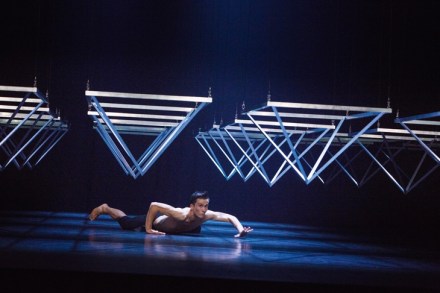

Adapting ballets out of plot-heavy novels set in fantasy locations and populated with multiple characters is a rubbish idea. The profound truth of such a proposal is forcefully borne out by the wretched muddle of Wayne McGregor’s MaddAddam, an over-inflated farrago drawn from a triptych of visionary fictions by Margaret Atwood. McGregor – hugely talented and energetic as he is – needs to calm down and slow down and think small Where to start? Apocalyptic themes – political, environmental and ‘societal’ – are evoked in images and spoken narration without McGregor having any means in his hyperactive choreographic vocabulary to translate them meaningfully into dance. Only those who are already