Hex appeal: the rise of middle-class witches

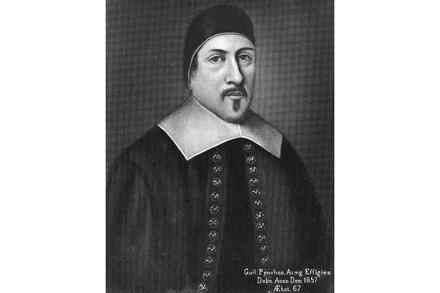

In King James VI of Scotland’s Daemonologie, written in 1597, he vigorously encourages witch-hunting and, in particular, the tossing of witches into the sea. Only the innocent would sink. As a way of identifying witches, it was clear and presumably efficient. These days, we have no such clarity. But witches walk among us. I’m not talking about women in black pointy hats, but something far scarier: the middle-class witch. In the past, she might have been called a depressive, a spinster or a divorcée. Now, she’s probably a middle-aged woman in the Home Counties with a TikTok account, a litany of spells and deep trauma. Modern witchcraft has always invited