Greater love, as wags responded to Harold Macmillan’s “night of the long knives” reshuffle, hath no man than that he lay down his friends for his political life. Well, Nicola Sturgeon’s political life is not threatened just yet but, even so, there was a whiff of this as she reshuffled her cabinet this week. If it wasn’t quite a night of long knives, it was certainly an afternoon of wee dirks.

The headline was the departure of Shona Robison, the health secretary, and one of the first minister’s closest political friends. Labour and the Liberal Democrats have repeatedly called for Robison’s resignation; yesterday they were given their prize. In truth, Robison has endured a rotten time and not just in terms of her professional responsibilities. Her marriage was destroyed by the infidelity of her husband, the Dundee East MP Stewart Hosie, and both her parents died in the past year. A step back is an opportunity to regather herself. Most people, recognising her as a transparently decent person, will wish her well.

Even so, SNP insiders did not dispute the fact Robison’s resignation was not an entirely mutual affair. In a number of areas the Scottish NHS performs better than its counterparts elsewhere; it remains under significant pressure. Targets are missed as a matter of routine; health boards continue to struggle to live within their budgets. It is creaking and it will not get very much better any time soon for the problems are systemic and structural. A new ministerial team, led by Jeane Freeman, a former advisor to Jack McConnell, who defected to the SNP in 2014, may help; it is unlikely to transform the service. Still, Freeman is, as she would allow herself, a tough cookie.

Elsewhere, there were returns to the cabinet for Mike Russell, the Brexit minister sacked from the education brief when Sturgeon became first minister in 2014 and a promotion to the justice brief for Humza Yousaf, who previously served as minister for transport. The economy brief was rolled into the finance portfolio, meaning that a new job had to be found for Keith Brown, the SNP’s new deputy leader: he has been demoted to the post of campaign director, charged with organising the 2021 Holyrood election and, of course, keeping the party on a war footing for a second independence referendum that is not going to happen any time soon. Angela Constance, a minister whose responsibilities almost no-one can recall, was also sacked.

Still, this was a necessary reshuffle. The Scottish government’s website made reference to a “refreshed” cabinet, thereby admitting its predecessor was obviously tired to the point of being knackered. Most of all, it introduced new blood to the junior ministerial ranks.

Seven of the nine new junior ministers were first elected in 2016 and their presence in the government is both necessary and a reminder that the nationalist torch will soon be passed to a new generation. The likes of Ash Denham, Kate Forbes and others are the future. Before this reshuffle, most of Sturgeon’s cabinet had first been elected in 1999 and most had served in ministerial posts ever since the SNP was first elected in 2007. That has given the Scottish government plenty of cohesion and stability but also stalled any succession planning. Still, there is something to be said for a cabinet whose members trust each other, and in this regard the SNP caucus at Holyrood offers something of a contrast to Labour and the Conservatives at Westminster.

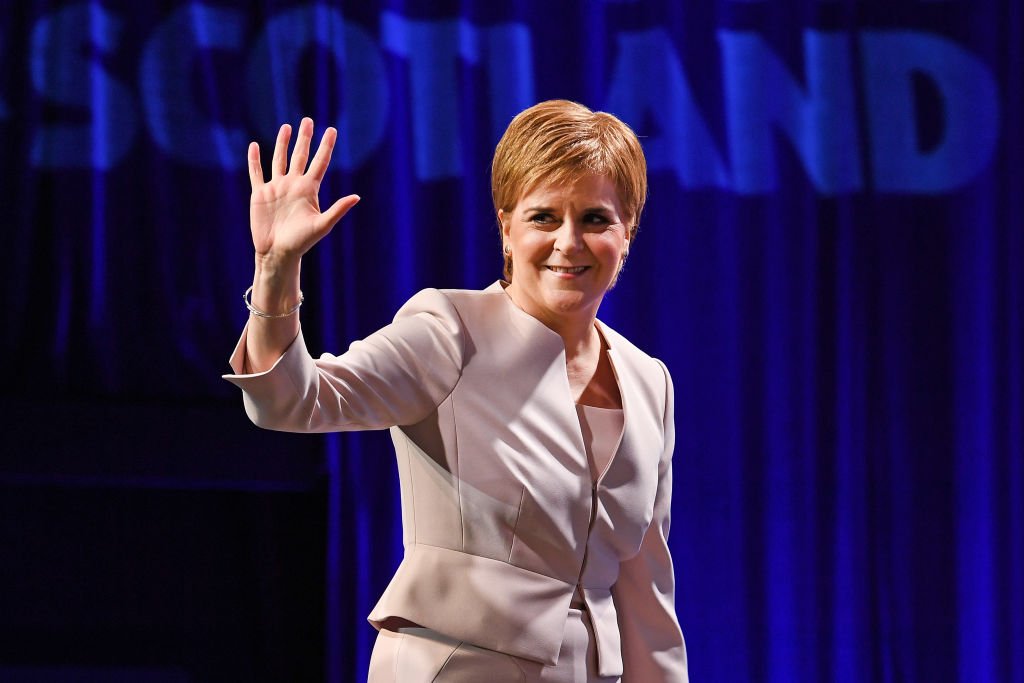

Sturgeon herself was long the obvious successor to Alex Salmond but the identity of her own eventual replacement has been much harder to ascertain. She has been, and for the time being remains, the SNP’s indispensable figure. Building one or even two winning teams is one thing; reinventing a government a third time quite another.

It is, of course, desperately early to be thinking along these lines, but this reshuffle begins the process by which you can begin to see how, after a decade as first minister – and a whopping 17 years in government – Sturgeon might step down in 2024, having groomed a successor who would then have ample time to prepare for the 2026 Holyrood election. Other futures are available, of course, but this is one of them.

Granted, that assumes the SNP will win the 2021 Holyrood election but do so without the kind of parliamentary supremacy that would allow the party to force a new referendum on the national question. The former seems likely, barring some significant shift in the opinion polls, the latter is, at present, something close to a toss-up. The margins between decent success and transformative victory are mighty thin.

Of course a referendum might yet happen before 2021. Sturgeon must push that door again to see if it will open. But as matters stand there is no indication it will. The first minister’s approval ratings have dipped into negative figures but, after 11 years in office, her party still commands the support of four in ten Scottish voters. That’s quite remarkable even if it is also a reminder that identity, more than policy, continues to be the dominant driver of Scottish politics.

Still, just as the SNP’s complaints about a Westminster “power grab” on devolved responsibilities followed hot on the heels of Sturgeon’s suggestion her supporters cease “obsessing” about the timing of a referendum – i.e. it ain’t happening soon, comrades – so this reshuffle was conveniently timed to coincide with the withdrawal of the Scottish government’s education bill that was, as recently as six months ago, both vital and the centrepiece of the SNP’s legislative agenda. Education reform, notionally the great priority and defining mission of this administration, has run into the entrenched and vested interests of Scotland’s small-c conservative education establishment. John Swinney, the education secretary, has blinked and backed-down.

Absent constitutional politics, however, there remains the risk that the SNP is reduced to mere managerialism. The party would, of course, dispute that. But its reforming zeal is often more a matter of rhetoric than action and, even when put into practice, suspiciously correlated with the number of people likely to be affected by its actions: when the numbers are small – landowners for instance – the SNP will be bold; when they are large – health, education etc – the nationalists favour a more cautious, or if you are kind, pragmatic approach.

Such are the costs of being a “national” party that must be all things to all people; a party that must persuade 50 per cent of the electorate to one day go on a journey with the SNP. Even so, however, Sturgeon’s new ministerial team has a stronger look about it than last week’s cabinet did. It is a reshuffle to refresh the Scottish government but also one that begins the process of passing the flaming torch of nationalism to a new generation.

Comments