What happens when a torrent of exceptional male stars leave the stage and flood the jobs market? Especially in a world when classical ballet appears to be becoming less fashionable, eclipsed by contemporary fashions and nervousness about audiences?

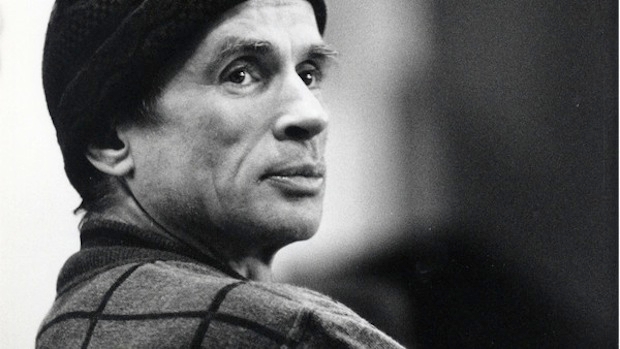

The titan of the Royal Ballet and Bolshoi, Irek Mukhamedov, was renowned at Covent Garden in the Nineties for his unique combination of muscle and gentlemanly manners, and if English National Ballet’s men are looking particularly refined on their winter tour of Swan Lake and Coppelia it may well be the result of his stellar coaching last month.

ENB’s director Tamara Rojo invited him over from Slovenia, where he has been running the national ballet, to hand on some of his precious knowhow to her young team of new male soloists. It’s impossible to overestimate the impact in London of Mukhamedov’s arrival in 1989. Most of all, he generated a new forcefield in the last years of the choreographer Kenneth MacMillan – who created Winter Dreams for the romantic Irek and The Judas Tree for the terrifying, brutish Irek, and both were united in his unforgettable performing of MacMillan’s Mayerling. But also the Russian showed that it only takes willpower and a sense of inquiry to transform yourself from a world-famous Moscow hunk into one of the greatest Albrechts in Giselle of living memory.

Here is a video double-helping of Irek’s streamlined partnering and charisma, first powerlifting in his signature Bolshoi role of Spartacus, filmed with the gorgeous Lyudmila Semenyaka in 1990 just before he suddenly quit Moscow for London – and then elegantly smooching in Manon at the Royal Ballet with the kittenish Viviana Durante a couple of years later (this is an illicit spectator video – the only record, it appears, of that period’s most memorable partnership).

Russian Irek in Spartacus, Bolshoi Ballet

Anglicized Irek in Manon, Royal Ballet

Having quit the stage, the mighty Mukhamedov hasn’t been able to reflect his dominance as a dancer in his subsequent career. He’s directed the Greek and Slovenian national ballets, somewhat fragile organizations in unstable economies. Yet what’s striking is that he isn’t unusual among a fabulous generation of male ballet stars who’ve recently left the stage – the like of which surely hasn’t been seen for decades.

Here’s a selection of stellar names from the post-Nureyev boom – Mukhamedov (now 54), Laurent Hilaire (52), Manuel Legris (50), Peter Boal (49), Nikolaj Hübbe (47), Julio Bocca (47), Vladimir Malakhov (46), JoséManuel Carreño (46), Igor Zelensky (45), Thomas Edur (45), Johan Kobborg (42), Nicolas Le Riche (42), Ethan Stiefel (41), Carlos Acosta (41), Angel Corella (38). You’ll probably want to add others, but that’s 15 already who qualify as (as the critic Alastair Macaulay once vividly listed) heroes, poets, gods, dreamboats and hunks. Even in comparison with the Nureyev-Bruhn era, can there ever have been such an astonishing flowering of charismatic men in ballet?

Hardly any of these exceptional artists can be found at the helm of what from the British perspective is a premier-league classical company – only the Royal Danish Ballet (Hübbe), then perhaps Berlin Ballet (Malakhov till this year), Moscow’s Stanislavsky (Zelensky), Seattle’s Pacific North-West Ballet (Boal), and the Royal New Zealand Ballet (Stiefel till this year), has occasional touring profile here.

But look at the quality of stars now in places like Romania (Kobborg), San José (Carreño), Estonia (Edur), Pennsylvania (Corella), as well as Slovenia (Mukhamedov). These are minor-league companies numbering up to 45 dancers, hence effectively unable to stage a full corps de ballet, and obviously dependent on the lustre of their artistic leader to draw in a big-name choreographer. Zelensky’s Novosibirsk berth and Bocca’s in Uruguay both give them strength in numbers (the Siberian troupe is state-supported, the Uruguay ballet is supported by the national broadcasting organization SODRE – anyone for a BBC Ballet?), but their distances from the world dance capitals limit their touring and hence their drawing-power.

From left to right:

Peter Boal (Seattle), José Manuel Carreño (San José), Angel Corella (Pennsylvania), Julio Bocca (Uruguay), Carlos Acosta (Cuba), Thomas Edur (Estonia), Manuel Legris (Austria), Johan Kobborg (Romania), Irek Mukhamedov (Slovenia), Igor Zelensky (Siberia), Ethan Stiefel (New Zealand)

Given the huge numbers of ballet companies around the world (in the US alone there are 129), it seems, does it not, that the top stars should have no trouble landing the top jobs? Well, it doesn’t follow. Recent appointments at flagship state companies such as the Royal, Paris, the Bolshoi and Mariinsky have shown a move away from stars, and towards managers and choreographers – more collegiate figures.

The repertory companies have had their fingers burned by superstar directors of the past. Nureyev was probably unique in being as great a director (in Paris) as he was a dancer – his own contemporaries, the Royal Ballet’s Anthony Dowell and Bolshoi’s Vladimir Vasiliev, the supreme dancers of their companies, were both underwhelming directors, and Mikhail Baryshnikov’s tenure at American Ballet Theatre was muddied by his position as dancer-director.

This year Hilaire and Le Riche, Paris Opera Ballet’s supreme stars of the past 20 years, quit their home company after the appointment as chief by Benjamin Millepied, a fashionable dancer-choreographer most famous for his horrible choreography for his wife Natalie Portman in Black Swan. Yet again, super-intelligent and gifted artists were left on the side of the highway.

Now, I don’t argue for a moment that office promotion must follow a fabulous performing career – my question here is about the need for a rightly nervous classical ballet world to benefit from this tidal wave of historically astonishing male artistry, rather than seeing it dissipated into running small companies where the energy may not survive local conditions.

One or two of these gods might indeed emulate the rare Nureyev transmigration from mighty performer into mighty artistic director, but most will not. Yet all that performing expertise must not be wasted, it somehow needs passing on to the generations of today’s young dancers who’ve been glued to these great stars on YouTube. Rojo’s invitation to Mukhamedov to coach was a small but vital step to see that the post-Nureyev boom was the start of something, not the end of it.

Comments