If you write about the mentally ill – people who suffer a short breakdown, maybe, or long periods of crippling stress – or say that those who must cope with autism, depression or schizophrenia all their lives are “handicapped”, you will be hammered. But not by the state and its supporters, or by members of the public with deep and prejudiced fears about mental illness.

You can say the health service is impoverishing care for the mentally ill because its administrators know they are an unpopular minority, who can be hit without a political cost. You can write about how the criminal justice system is imprisoning vast numbers of minor offenders whose sicknesses ought to be treated in hospital. No one in authority will mind as long as writers do not write so strikingly that they stir what public conscience there is. The preposterous truth is that the state and the judiciary do not need to police language. Mental health charities and activists patrol it instead. Bureaucracies and most news organisations follow their codes without question. Here from several sources is a rough but I hope fair summary of the “dos” and more particularly the “don’ts”.

You should never use words that have become insults – “lunatic”, “nutter”, “unhinged”, “maniac” – even if they were not originally insults or are not always used as insults now – as is the case with, “mad”, “simple”, “cripple”, “retarded” or “disturbed,” for example. If I were to write that the police hounded a simple man because charging him would help them hit their arrest targets, readers would have a picture of official harassment in their minds in seconds. If I were to talk about depressed women in prison, who are so afflicted by mental illness they are close to suicide, readers would know that I was describing a routinely misogynist criminal justice system. Plainness brings clarity. But clarity won’t do. Nor will basic descriptions. You should not say “the mentally ill” you should say “mental health patients”. You should not say that someone is “suffering” from a mental illness (or depression, schizophrenia or autism) or that he or she is a “victim” of mental illness or is “afflicted” by mental illness. You should say that he or she “has mental health problems” or is “a person with mental health problems”, a member of the collective properly known as “people with mental health problems”.

It may not seem onerous to insist on “people with mental health problems” rather than “the mentally ill”, but writers abhor clunky phrases and superfluous words. They are also rightly suspicious of all who tell them what they can and cannot say, and not only for egotistical reasons.

As he lay dying from motor neurone disease, Tony Judt retained enough intelligence to know the falsity of the soothing words he encountered:

‘You describe everyone as having the same chances when actually some people have more chances than others. And with this cheating language of equality, deep inequality is allowed to happen much more easily.’

If you do not say people “suffer” from or are “afflicted” by sickness then you please those who would restrict the funding for treatment, or cut disability benefits, or pack off confused minor offenders to prison rather than hospital. At best, you are talking about people who have brief bouts of mental illness, as many of us will, whose dislocation is temporary. At worst, you patronise people who need help all their lives with a tongue-biting euphemism, which covers up suffering in the name of avoiding stigma.

“A person is not the sum total of the symptoms that they experience, these can vary greatly from individual to individual and nor are all individuals always symptomatic” explained one advocate of “positive” language. He was right to an extent. If a brief bout of mental illness afflicts you it is “stigmatizing” and “disempowering” to say that your sickness is all there is to you. It never occurred to him, however, that how defining symptoms are depends on their severity. The more severe they are the more defining they will be.

Another supporter of euphemism was honest enough to declare her opposition to accuracy in language. “Does ‘I am suffering from… dementia, arthritis, cancer, MS etc’ sound more negative and less empowering than ‘I am diagnosed with…’? Whilst the term suffering may technically be ‘correct’, I cannot see how anyone could not see it is not negative and disempowering.”

Like so many others she believes that you can change the world by changing language, a fallacy that is everywhere hobbling radical movements. If accuracy is sacrificed, they say, if basic descriptions such as “mentally ill” and “sufferer” are forbidden, if readers and listeners get lost and woolliness is held up as a model to writers and speakers, so be it. Waffle will lead us to a better future.

And because the desired change to the world is for the better, few decent people want to object. Newspapers, broadcasters, universities and government departments accept speech codes banning words that allegedly generalise, insult or disempower, even when the impotence-inducing insult is impossible for the untrained observer to see.

The political stupidity of providing solace to those who would remove public support for sick men and women should be obvious. Why should the taxpayer give money to empowered adults, whose ailments vanish in windy subordinate clauses or hide in a circumlocutory maze? Why should judges treat them differently from any other offender in the dock? But the folly does not end there.

The notion that you can change the world by changing language gets history upside down. Language changes as the world changes, not the other round, and I cannot see how you can take the lazy course and speed up the fight against prejudice by fiddling with words, when the real problem is malice. Even in the case of words that appear clear insults, everything depends on the intent of the user. Is he or she malicious or benign? The handicapped man bullied at work and the child bullied at school know it, as do all who attempt to “reclaim” language. From “suffragettes” to “queer”, groups of second-class citizens have taken the abuse thrown at them and used it for their own purposes because they understand that motive matters more than labels.

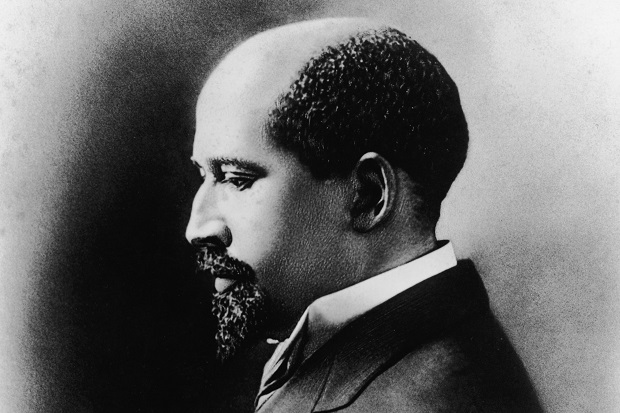

In 1928, the great American civil rights campaigner W.E.B. DuBois, put the argument best after he received a letter from a young activist, who was appalled that DuBois and his comrades were happy to use the word “negro”. Negro was a slave name, he said, which should be abolished. DuBois told him to toughen up and concentrate on what mattered.

‘Do not at the outset of your career make the all too common error of mistaking names for things. Names are only conventional signs for identifying things. Things are the reality that counts. If a thing is despised, either because of ignorance or because it is despicable, you will not alter matters by changing its name. If men despise Negroes, they will not despise them less if Negroes are called “colored” or “Afro-Americans…” It is not the name – it’s the Thing that counts. Come on, Kid, let’s go get the Thing!’

The reason people accept bans is that labels matter to activists, who believe that designation is destiny. What are you to do when they confront you? If they say they want you to change the way you refer to them, it is only politeness to agree. If they say that your language fuels racism, sexism or any other -ism you deplore, you will give way sharpish, because you will be accused of the very vices you condemn. No one wants that kind of trouble, so they fall into line and cover sickness with sickly euphemism.

It doesn’t work. If it did, then once language changed prejudice would change with it, and there would be no need for further alterations. But the urge to rewrite is constant. There is never a moment in mental health when anyone can assure you that this change will be the last. Half the words now on the banned list were kindly meant in their day. “Spastic” was once such a respectable term that in the 1960s Britain’s cerebral palsy charity called itself the Spastics’ Society. It changed its name because “spastic” became an insult, as every term for mental handicap becomes an insult.

The persistence of prejudice guarantees that today’s approved words will become insults too. One day they will be branded as stigmatising and disempowering and be changed again. If you forget that it is not the language but the fact of prejudice which is “the Thing that counts” you condemn yourself to endless linguistic revision.

As you revise, you lose sympathisers. There is a particular type of heresy-hunter, prominent in the universities and public sector bureaucracy, who delights in pulling people up on linguistic slips. I cannot tell you how many good people they drive out of left-wing politics. They are sincere, they want to see political change, and some snuffling, pointy nosed witch-finder accuses them of siding with the enemy because they did not realise that words which were acceptable yesterday are unacceptable today.

To stop them walking away you must accept a small paradox: if you want to be radical in your politics, you must be conservative with your language.

Comments