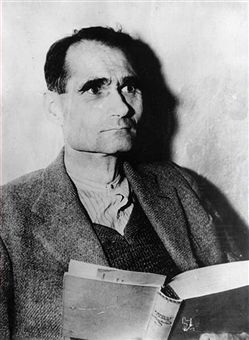

An obvious comparison can be drawn between Moussa Koussa and Rudolf Hess. It is

intriguing but easily overextended. While Koussa’s sense of self-preservation is palpable, Hess’s flight at the high tide of Nazism remains unfathomable. Back in May 1941, a onetime

prominent Nazi and man of letters called Dr Hermann Rauschning, a controversial oddity in his own right, analysed the Hess mystery for

the Spectator. (Incidentally, the British secret service file on Hess will be released in 2016.)

An obvious comparison can be drawn between Moussa Koussa and Rudolf Hess. It is

intriguing but easily overextended. While Koussa’s sense of self-preservation is palpable, Hess’s flight at the high tide of Nazism remains unfathomable. Back in May 1941, a onetime

prominent Nazi and man of letters called Dr Hermann Rauschning, a controversial oddity in his own right, analysed the Hess mystery for

the Spectator. (Incidentally, the British secret service file on Hess will be released in 2016.)

The Rudolf Hess Mystery, 16 May 1941

The flight of Rudolf Hess to enemy country in the middle of the war is more than a lost battle for Hitler. It must be a desperate blow for him, at the zenith of his military development, not only to lose his most faithful and unselfish colleague, but to see him seek refuge with the enemies of National Socialism. For the German people, certainly not intoxicated with victory, but oppressed by doubt and fear, it is an event which reveals as a grim reality what has hitherto been feared – Germany on the edge of an abyss. It is an event like the battle of August 8th 1918, when the German troops refused to attack. In this case the pick of the Party, an irreproachable German patriot, refuses to collaborate further. One event, like the other, is a lighthouse which cast its beam far.

We must expect the German propaganda to be busy with the affair. The rumours will not be silenced. No new success can make up for this. Uncertainty and doubt will henceforth attend everything done by Germany. It is no ordinary man who opposed Hitler in this dramatic fashion. It is the man who, alone perhaps, could have taken such action. In this or that case the rumour would spread that the man had acted only from selfish reasons. But Rudolf Hess, whatever else may be said about him, was the only honest personality among the leading National Socialists. Everyone in Germany knew that he sought to serve Hitler and the German people to the best of his ability. With Hess, people will say in Germany, Hitler loses his only unselfish adviser and his good genius.

But how can one explain a decision on the part of so diffident and apparently irresolute a man? It was seemingly well prepared and well thought out. Might it not even be a trap? Might not Hess have been sent by Hitler as the first of a Fifth Column? Certainly that suspicion leaps to mind. But on closer consideration such an explanation seems improbable. The very doubtful success of such a mission would be in no way proportionate to the damage done in Germany by Hess’s apparent desertion.

Is the whole affair, then, just a quarrel inside the leading clique? The struggle for leadership and influence among the members of such as conspiracy is always a fight to the death. In certain circles there is a tendency to liken this affair to typical disputes among gangsters and revolutionaries. Possibly Goering is jealous of Hess and wants his post. Possibly it is Himmler. That, if it were true, would not be enough to give the episode the significance it seems to wear. The true motives of this flight are obviously different. I must confess that for a long time I have been expecting such a sign of the change that is beginning among the German people.

The complete unity of the German people can be exaggerated. A mighty system has been built up, nothing more. Such a system is prolific of crises and has no power of regeneration. It is not only out of fear of the loss of civic rights or life itself, but from a misunderstanding of one’s duty that this unhappy state of things has so long prevailed.

Up to a point, Hess’s case is typical. He has always been torn between the belief in his friend and his duty to his nation. He has warned and he has opposed, though prudently. Hitler used to bellow at him. His rivals cast suspicion on him. He saw the net narrowing. In the end, some new reckless act on the part of Hitler impelled him to overcome the restraint imposed by his hesitating temperament and take a supreme risk.

What can it have been which, so to say, upset the apple-cart? I do not know, but I could make a good guess. I have long asserted that one might count on war between Germany and the Soviet Union. But Hess’s flight seems to me to have a bearing on this. Hitler is preparing another move. Perhaps it is a close alliance, possibly even a commercial union, with Soviet Russia. It seems to me that Hess’s political views would lead him to protest passionately against such a policy. It may well have been the last outrageous step which he found intolerable.

On the other hand the explanation may simply be his insight into the desperate condition of Germany, which he was better able than any else to judge. As a despairing patriot he sees Germany’s downfall; in his anxiety for the future he is not alone: Hitler’s last speech shows that clearly enough. Why did the Fuhrer conceal the truth about the Balkan losses? Why did he lay so little stress on the achievements of the German troops in the Greek campaign? Because the war against Greece was so unpopular and everyone was opposed to rescuing the despised Italians. There are two kinds of people concerned in what they call in Germany the National Revolution: desperados and despairing patriots. The men of the second type must not be overlooked. Certainly Hess was one of them. And there are many among them who today wear the swastika and the Party uniform under compulsion. These despairing patriots should be won over. That would be a great achievement, counting for much more than merely gaining a mass of man who play no decisive part.

Whether this is really the beginning of the breakdown in Germany may well be questioned. But it is unquestionably a proof of the inner weakness of this system that appears to be so strong, and it would be politic not to wait passively for the sequel, but to turn the episode to the fullest advantage.

Comments