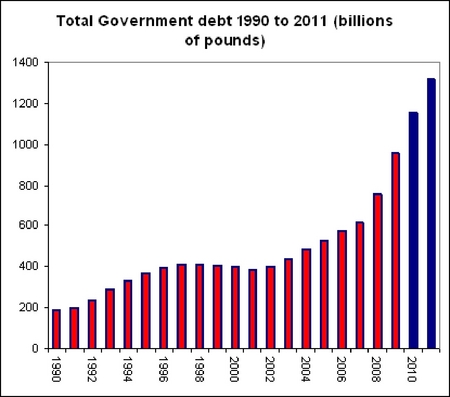

The UK debt crisis has three constituent parts – household, government and banking. The fact that households, government and banks all went on a debt binge at the same time makes the risks for the UK economy so unusual. The European Commission is now estimating that total UK Government debt will rise above £1.3trillion by the end of 2011, representing a more than trebling in the total debt load since 1997. If interest rates normalise to the 5% or so seen during recoveries in previous cycles, this will see the interest service bill alone rise to around £65billion a year – more than double the total defence budget. Assuming continuing to print money to fund the deficit is not a option, an increasingly substantial part of UK financial resources will have to be diverted away from education, welfare and investment to pay for the cost of the debt explosion through this recession.

Household debt has more than trebled over the past decade – rising from just under £500billion in 1997 to almost £1.5trillion in 2008. Each adult in the UK has an average debt of £30,221, more than 130% of average annual income. Households are now paying a bill of over £65billion a year just to cover the interest costs of this debt.

Many economists – and the Government – continue to argue that the UK can handle a much higher Government debt burden, citing Japan and some other EU economies, such as Italy, as examples. The key difference with those countries – Japan in particular – is their much lower level of household debt and higher domestic savings. As Governments ultimately only get money from one place– taxing their citizens – Government debt is a claim on households. Paying attention to the total sum of household and Government debt is extremely important for this reason. When households are highly in debt with low savings themselves, the money to finance Government deficits either has to be printed or borrowed from abroad. This is why more experienced finance ministers know that Governments should be saving when their electorate is borrowing. There are very few precedents globally in the last few decades for a Government to join in a private sector debt binge in this manner. Given the huge financing needs of the UK Government – likely to be around quarter of a trillion pounds a year when maturing debt is included – the job of the Chancellor and Foreign Secretary is likely to become focused on securing Gilt buyers from reserve managers in capitals like Moscow, Beijing and Riyadh.

The further 40billion pound bailout needed for some UK banks last week provided an important reminder of the costs that are involved in absorbing the losses of the UK banks around the world – the third leg of the UK’s debt crisis. As Fraser Nelson has pointed out, the bank “rescue” was largely a case of the banks taking over the taxpayer. The Bank of England estimates that British banks have over $3.7 trillion of lending exposures around the world. With the IMF warning that more than half of the £380billion they believe the UK banks have lost in their global adventures has still to be recognised, the risks that further calls upon the taxpayer will need to be made are significant.

The combination of this perfect storm of debt problems will require an immense amount of economic and political skill to manage a path back to sustainable finances, and avoid a very material decline in living standards.

Comments