‘To have a father is always big news,’ according to the narrator of Sebastian Barry’s early novel, The Engine of Owl-Light. Stephen Dedalus puts it differently in Ulysses: ‘A father is a necessary evil.’ But later, he qualifies this: ‘Paternity may be a legal fiction. Who is the father of any son that any son should love him or he any son?’ Colm Tóibín has repeatedly squared up to fathers as well as mothers in his own work (a dead father haunts the family in Nora Webster, and fatherhood is a central theme in The Heather Blazing). His new book takes on the theme of fatherhood in relation to three great Irish writers, supplying a scintillating new perspective on each.

It is three meditative essays, extended versions of lectures given in memory of Richard Ellmann, the legendary biographer of Joyce as well as of Yeats and Wilde; lucky BBC listeners will have heard Tóibín reading them, with controlled passion, on Radio 4. The published version comes with the welcome grace note of a long introduction, which describes a Bloom-like walk around the part of Dublin associated with his chosen writers (Merrion Square, Westland Row, Clare Street). Tóibín’s focus on Dublin is intensely personal, autobiographical, atmospheric. As with the memoir by his fellow Wexford man John Banville, Time Pieces, there is a kind of fierce possessiveness at work here, as well as an elegiac memory of the sleepy city he came to in the 1970s. There are also gimlet-like reflections on writers who preoccupy him (Beckett, Gregory, Synge, O’Casey as well as Yeats and Wilde), not least their ancestral Protestantism. It meant little to them in terms of religious practice (except in Gregory’s case), but inflected the way they were perceived in Ireland. ‘It must be fun,’ reflects Tóibín, tongue-in-cheek, ‘not believing in anything, and having your fellow countrypeople wanting you to clear off to England because of the very religion you don’t believe in.’

The introduction also teases out the ways in which the lives and works of Wilde, Yeats and Joyce interpenetrated each other: Wilde (and his mother) taking up the young Yeats in London; Yeats helping Joyce at the outset of his artistic odyssey; references to Wilde and Yeats threaded through Ulysses. But what preoccupies Tóibín above all are the parallels between the three writers’ relationships with the fathers, whom they spent much of their lives getting away from. And then there are the similarities between those fathers, each of whom provided a kind of inspiration as well as an awful warning.

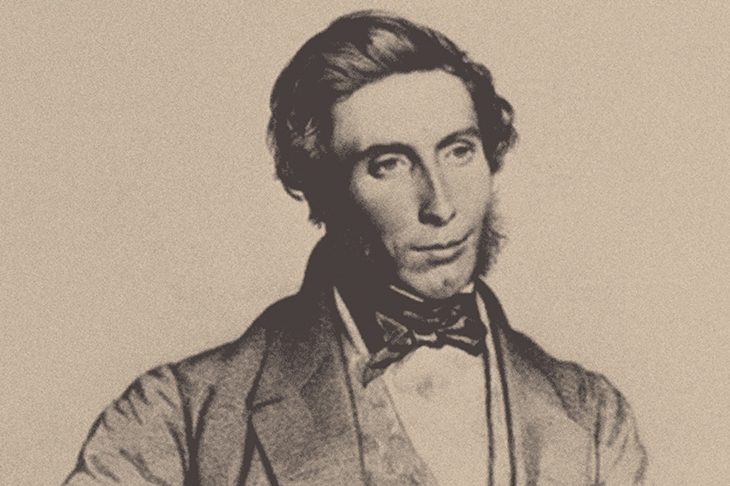

Wilde’s father, a celebrated polymath with notable achievements to his credit in medicine, archaeology, antiquarianism, topography and folklore, was eccentric and pursued by scandal; other biographers have drawn attention to the court case brought by a young woman who claimed to have been sexually molested by him, and also to the illegitimate children he sired. Tóibín reflects on the duality of Irish existences in the Victorian age, before shifting the perspective by emphasising Oscar’s pride in his parents and their achievements, counterpointed by his cultivated contempt for Queensberry, his lover Bosie’s father, and the author of his downfall.

The Wildean text which reflects this is, of course, De Profundis, and Tóibín weaves into his narrative his own experience of reading this long manifesto out loud in Reading Gaol, where it was written, as part of a literary festival. But he also conjures up the young Wilde, accompanying his father on archaeological field trips, and growing up in a house where ‘the idea of loyalty, whether to the Crown or to Victorian sexual mores, was never stable’.

The chapter on John Butler Yeats similarly indicates the lifelong influence that this charming, brilliant, wilfully unsuccessful artist had on his eldest son, as well as on three other formidable siblings. The elder Yeats’s inability to finish a painting was noted by W.B. Yeats, whose own work embodies, by contrast, perhaps the most resolute signature-lines in modern poetry. But W.B. also testified that much of his education came from the conversations overheard in his father’s studio, and the old man was one of the most brilliant talkers of the age. His letters, which mingled profound philosophical judgments with piercingly funny asides, were already being collected for publication in his lifetime, and Tóibín does them full justice.

They become especially important after John Butler Yeats’s escape to New York for the last 14 years of his life, when Tóibín concentrates on the love letters sent to Rosa Butt, his great unfulfilled love. Tóibín arrestingly compares these passionate, assertive, sexually frank epistles to W.B. Yeats’s late poems, where the poet proudly declared himself ‘a foolish, passionate man’ and railed against the indignities of old age.

Finally, we encounter Joyce’s father John Stanislaus Joyce, who haunts his son’s work and is generally thought of as a selfish wastrel whose inadequacies propelled his family rapidly down the social scale. Some of this is undeniable, and his namesake other son Stanislaus hated their father with a chilly and unforgiving disdain. But Tóibín subtly and movingly traces the changing presentation of John Stanislaus through James Joyce’s work, pointing out that Simon Dedalus in Ulysses is treated with far more sympathy and respect than the father of the eponymous Artist in Portrait. Even at the surging end of Finnegans Wake, as the river runs to the sea, the invocation to ‘my cold mad feary father’ is undercut by a child’s cry, piercingly authentic: ‘Carry me along taddy like you done through the toy fair!’ It is one of the few moments in the exasperating Wake which bring a catch to the throat. By contrast Tóibín’s book is accessible, imaginative, enlightening and powerfully moving throughout.

Comments