I’m not a critic, I’m an enthusiast. And when you are an enthusiast you need to try your best to keep it in check when writing reviews, just in case your prodigious levels of excitement and, well, enthusiasm, threaten to overwhelm readers and only succeed in putting them off. Because people generally need a bit of room — to create some distance, establish a tiny bit of breathing space — in order to make their own considered decisions about the liable goodness or badness of a thing.

But shucks to all of that. Because I have to say this — I need to say this — out loud, in print: Navid Kermani has written one of the funniest, most perceptive, outrageous and engaging books about art, life and faith that I have ever read (and these are the kinds of books I most love to consume).

There. Yes. It’s wonderful. It’s cathartic. It’s transformative.

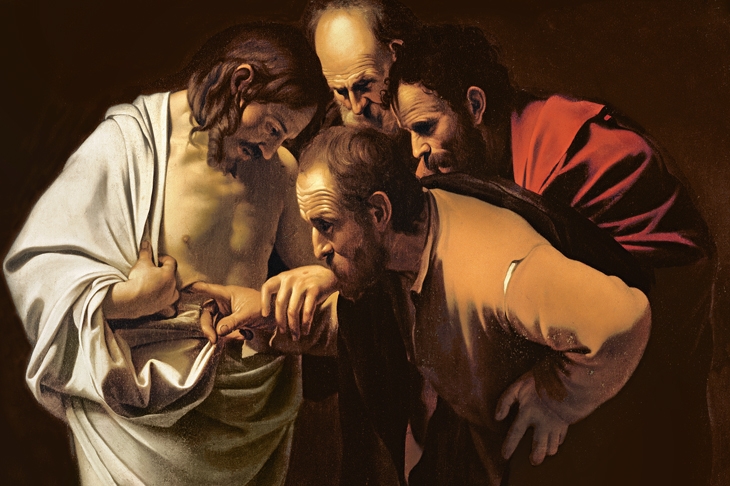

The premise of the book is a simple one: Kermani goes to look at some of the most significant (and not so significant — but still interesting or contentious) objects of Christian art in the world and boldly holds forth on them. He is a Muslim. He is of Iranian origin, but has lived much of his life in Germany. The book is translated — a couple of clunky moments in the first few pages and then, wow — just wonderfully. He is easy to read, but his insights are fierce and acute. What do I know of Montaigne, you ask? Very little, I answer. But enough to say that these charming, informal, clever little essays — which cohere almost effortlessly into a breathtaking whole — stylistically and emotionally remind me most of him. There can be no greater accolade, surely.

Kermani is an intellectual and a novelist. He brings the finer attributes (and, let’s be honest, not all the attributes of intellectuals and novelists are fine, by any means) of both of these into this work. Most of all, he brings a sense of innocence and mischief. He is very human. He is unapologetic and — a thing so precious in writing on faith — free. He is fearless. Just like so many of the artists — and the religious, both past and present — he engages with. What a rare thing! What a wonderful thing! How on earth did he get there?

It’s only fair to warn potential Catholic readers that the second chapter is very likely to offend. Kermani goes to look at a little statue of the Christ Child (Perugia, c.1320, Bode Museum) in Berlin and says a series of the most unacceptable things about it. He arms himself with the (non-canonical) Infancy Gospel of Thomas and really lets rip. He calls the Christ Child ‘a paragon of hideousness’, and this is the starting point for a whole lot of

wild hypothesising.

But it comes from a place of absolute sincerity, which makes the book compelling both for believers and for those who don’t or can’t.

If pushed, I’d say that what Kermani brings to the God debate is flexibility. It would be fair to call his work inter-faith. This notion tends to fill me with dismay and horror. It creates the idea of a fine meal liquidised. As if everything good and diverse and distinct may be lost — pummelled, by good intentions, into an ecumenical sludge. But this isn’t so. In fact it’s quite the opposite. Kermani talks about art and faith from his own singular, but refreshingly uninhibited, perspective. There is incredulity, but it is matched by an intense empathy. He is very nearly seduced. He can be reverential. Best of all, he is funny. A friend pees in a hedge. He has a bad cold. He dreams about his mother. He gets ridiculously overexcited.

If I have one caveat, it’d be that within the Catholic faith images are not celebrated or worshipped in and of themselves. They are mere representations of an idea — an otherworldly ideal (they are not idols — not that there’s anything wrong with worshipping idols, I hasten to add), and this ideal can never be matched in plaster or paint. The images merely bring a location, a focus, for devotion, creating a kind of mystical vortex. But their goodness or badness is, at some level, irrelevant. An ardent lover doesn’t care if the object of their devotion is wearing bad shoes, or has a spot on her chin. An ardent lover loves in spite of, not because of.

I wish I could do justice to what Kermani has achieved in his fine work with these, my clumsy sentences, but I can’t. Suffice to say that he needs to be read and loved and admired. Kermani’s book has challenged me and it has changed me. And this? This?! It’s a crazy rave review! Just in case you hadn’t noticed.

Comments