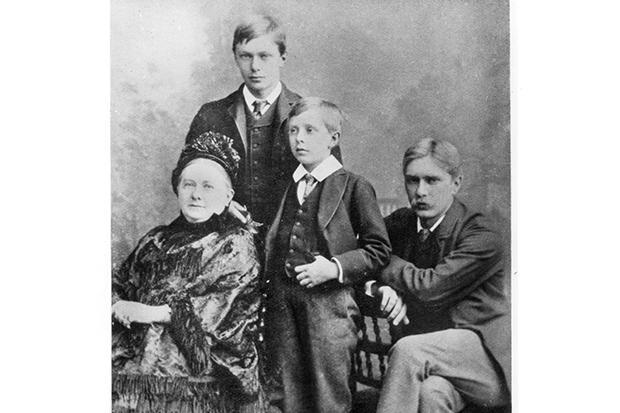

The Benson family was one of the most extraordinary of Victorian England, and they certainly made sure that we have enough evidence to dwell on them. Edward White Benson was a brilliantly clever clerical young man of 23 when he proposed to his 11-year-old cousin Minnie Sidgwick. He had been the effective head of his family since his father’s death nine years earlier; Minnie, too, was fatherless. Despite doubts from Minnie’s mother, they agreed to marry when Minnie was 18.

She, too, was clever — Gladstone famously described her as ‘the cleverest woman in Europe’ — but had no real attachment to Benson or to any other man. Her romantic passions were always directed towards women. Curiously, as Benson rose through the hierarchy of the Church of England, ending as Archbishop of Canterbury, Minnie Benson’s passions seem to have continued without abatement or comment. As soon as her husband died, she went to bed with Lucy Tait, the daughter of a previous Archbishop of Canterbury, and apparently stayed there.

Everyone seems to have known about this liaison and many others, and no one seems to have cared. One of Minnie’s sons, Fred, wrote about his mother and Lucy sleeping together much later; and created, too, as a sort of in-joke, a statuesque maid called Lucy, who catered to an enthusiastic lesbian painter, Quaint Irene, in his Mapp and Lucia novels. E.F. Benson — Fred’s publishing name — is now the best remembered of the Benson children; but all were extraordinary. None married. At least five of them were clearly lesbian or homosexual.

Arthur (A.C.) was a pillar of professional life, the distinguished editor of Queen Victoria’s letters, remarkably dull in his published work and remarkably intense in his unpublished diaries. He was famous for passionate friendships with Cambridge undergraduates: there is an adorable photograph here of the aged Arthur arm in arm with a young Dadie Rylands, working it. Nellie died young, but had a relationship with Ethel Smyth, who went through the Bensons, mother and daughters, like a dose of salts. Fred was the one Benson who really did not care about religion at all, as anyone who remembers the Scots padre in Tilling will realise. His indifference to God scandalised his siblings, though not, oddly enough, his saucy cheerfulness about gay and lesbian heroes and heroines in his likeably middlebrow fiction, from the lecherous school story David Blaize to the splendid lesbians who run off together at the end of Paying Guests.

Hugh appalled the family by converting to Roman Catholicism and becoming first a priest, then a Monsignor. He was an intimate friend of that sinister fantasist Frederick Rolfe, Baron Corvo, and wrote some bizarre novels intended to further the Catholic faith. Martin died very young, and some of the hopes of his father died with him. Finally, Maggie was an archaeologist and Egyptologist. Despite disliking and distrusting her mother’s lover Lucy, she moved in with the pair of them after her father’s death, bringing her own lover, Janet.

The family has attracted considerable interest, and some biographers. It’s been a while since anyone has attempted a book about the whole family, and the labour would be very daunting. A.C. Benson’s extant manuscript diary is three times the length of Proust; four of the children published at least 14 books about their own family. I’ve read quite a lot of E.F., but wouldn’t claim to have got through more than half of his novels. Between them, they knew absolutely everyone, from Queen Victoria to Elgar. (A.C. wrote the words to ‘Land of Hope and Glory’ and invented King’s College’s Nine Lessons service.)

This isn’t the biography, and actually suffers from the lack of the obvious thing to do — 50 pages telling the story of the six principal characters to frame the discussion. Simon Goldhill, who is professor of Greek at Cambridge, sets his cards on the table at the start by declaring biography ‘a ludicrous genre’, as ‘the attempt to summon up a life in neatly chronological prose is bound to be an expression of its own failure’. It seems a perverse decision, particularly since almost all the writing by the Bensons on which the book is based is not available to the reader — whether out of print, never printed or ludicrously vast in substance, like A.C.’s diary. Moreover, the small parts of the Bensons’ work that are available — E.F.’s delightful novels, for example, or the ghost stories that they all wrote from time to time — are passed over in silence.

Goldhill discusses three aspects of the Bensons’ lives, and inevitably it seems like a commentary on material that the reader doesn’t have much access to. None of them emerges clearly as personalities, or as proponents of intellectual positions in the way they do from even quite ordinary biographies.

First, Goldhill focuses on their attitudes to writing, and especially to the acts of confessional in an age where families were being examined in detail by writers from Philip Gosse to Samuel Butler and the Grossmiths.

Secondly, the vexed question of the Bensons’ sexuality is gone over. Goldhill points out, quite rightly, that identifying individuals as homosexual or lesbian is not quite appropriate for those living in the 19th and early 20th century. The vocabulary was only just emerging; very few people either thought of themselves in such a way or could actually consider such a thing was possible. Nevertheless, we know that individual Bensons did discuss what they called the ‘homo sexual’ issue between themselves, and labelled others as ‘homo sexual’. There is no doubt that most of them had concluded that heterosexual relations, and certainly marriage, were not possible for them. A.C. Benson, like Tchaikovsky, even acquired the traditional appendage of the distinguished homosexual, an immensely rich patroness, in a Madame de Nottbeck. Like Tchaikovsky’s Nadezhda von Meck, Madame de Nottbeck handed over large sums of money and stipulated that they were never to meet.

Lesbianism was less a subject of discussion, and how women might find sexual fulfilment remained a matter of the utmost bafflement to half the human race until the 1920s. When the Canadian Maud Allan sued an English paper which had described her as leading a ‘cult of the clitoris’ in 1918, the court heard that 23 out of 24 professional men who had been consulted had no idea what the clitoris was.

The third area of the Bensons’ interest is religion, but this seems too large a question for Goldhill. The archbishop’s contribution to the development of the Church of England, and Hugh’s curious religious personality (including his terrible betrayal of a conversion), the very strange novels and the friendship with the fantasist Rolfe need exploring with reference to an immense world of Victorian debate which we’ve more or less lost interest in. Most of Gladstone’s library — still open to the public — consisted of theology. There may be a market for discussion of the Bensons’ engagement with theological thought, but it does appear a very complex subject.

A book on the whole story of the Bensons ought to be a compelling one. But it seems especially odd to set one’s face against biography when it was the means by which most of the Bensons sought to understand their own existence — and when their ideas and their means of expression are now quaint at best, and utterly obsolete at worst. Goldhill’s book is generally solid, though not without blunders, like calling Edward Carpenter ‘Thomas’ and saying that Fred’s novels ‘parodied’ Rye, ‘the small and very conventional Sussex town’ he was mayor of. (You can parody a literary work, but only satirise a town.) It is strange to call their era ‘Victorian’ when some lived into the second world war. And there is no index, which, considering this is a very involved argument about several extremely active writers and personalities, seriously damages the book’s usefulness. It seems a curious way to approach a family whose lasting legacy, as Goldhill idiosyncratically refuses to admit, is Mrs Emmeline Lucas’s war against Miss Elizabeth Mapp.

Comments