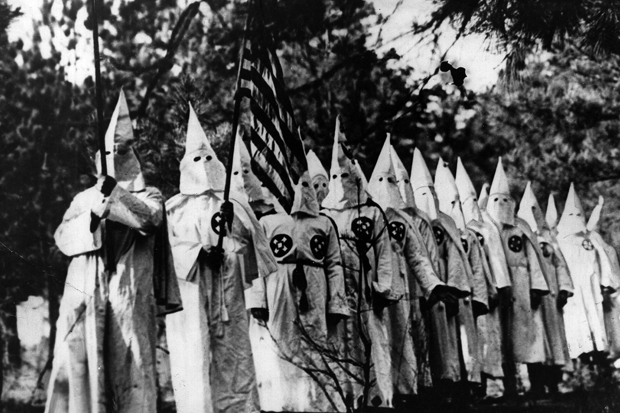

For the first time in living memory, a presidential candidate for a major party has received the enthusiastic endorsement of the Ku Klux Klan; one prominent former member of that fraternity — a Grand Wizard, I think: or was it a Grand Dragon? — is running for the US Senate. Members of the Black Lives Matter movement did not riot in Cleveland, but that is only because they were nearly always surrounded by troops of mounted policemen. It shouldn’t be surprising that some of us are looking back with hope and trepidation at the American Civil Rights movement of the 1960s.

One of the most remarkable books the movement produced is this 1973 family memoir, newly reissued with an afterword by the author. Paul Spike, an American-born old Fleet Street hand, is the son of the Revd Robert Spike, a pastor and activist who was found bludgeoned to death by a janitor in 1966 in Columbus, Ohio. The murder of Robert, who was at the forefront of the movement as director of the National Council of Churches (he even had a hand in writing some of Lyndon Johnson’s speeches), was never solved, though it was suggested by police that his homosexual activity — hitherto unknown to his family — rather than his politics may have played a part.

Reading Photographs of My Father is a kind of parallel Godfather II-like experience, except that the chronologies are reversed so that we witness the son’s rise, such as it is, through Columbia and therapy alongside the father’s fall from lobbying Congress and the White House to dealing with harassment from the FBI. It reminds us that if the past is a foreign country, the recent past can feel like Tristan da Cunha: Northern and Midwestern Republicans forcing Civil Rights legislation down the throats of recalcitrant Democrats in the South; Brooks Brothers-wearing Wasp clergymen with chronic digestive ailments at the vanguard of progressive activism; people taking existentialisms seriously.

Today it is easy to laugh off the spectacle of oceanographers-turned-lady bishops who deny the divinity of Christ and hold urgent conferences on the ‘immorality’ of climate change, but the political battles fought by the Revd Spike and other liberal Protestants half a century ago for the dignity of America’s black population were entirely laudable, whatever one thinks of their theology. (Many believers will shake their heads when they read Martin Luther King, in a telegram sent to the Spike family, praising Robert for having elevated ‘religion from the stagnant arena of pious irrelevancies and sanctimonious trivialities’, as if saving immortal souls were a parlour game, and at silly quotes from the latter about how ‘the Christian man thanks God for his sexuality’.)

This is very much a 1960s book in the best and, occasionally, worst senses. Spike himself comes across as a kind of stoner Holden Caulfield, bored, naïve, Camus-reading, basically decent, in whose triumphs — collecting 20 rejection slips before getting a story published in the Evergreen Review — we are effortlessly persuaded to rejoice. When he moans about having to take a Chaucer survey course alongside ‘Projects in Imaginative and Creative Writing’ at school and recounts the days when he would ‘sip beer and share a joint, soaking in the imagery’ of Blonde on Blonde, you know exactly where you are. There is a characteristic lack of reserve — did readers, now or in 1973, need to know about Spike’s sexual fantasies involving his mother?

This anniversary edition ends with an afterword in which Spike reviews information about Robert’s death brought to light by recent historians. He has followed names and leads to Ohio, Washington, and the online archives of the Johnson White House, but there is not much in the way of closure. After starkly pointing out that he has now ‘lived with [Robert’s] murder longer than I ever lived with him’, he confesses that he still has no idea who killed his father. His anger is, understandably, unabated.

Period eccentricities and the occasional overblown metaphor (years that ‘stick in America’s back like daggers’) notwithstanding, Spike’s memoir is as compelling as it must have been four decades ago. It is unsurprising that he has no plans to return to the USA.

Comments