Go to any bookshop — always supposing you’re fortunate enough to have any left in your neck of the woods — and chances are that lots of window space will be given over to two genres — children’s books and cookbooks. Step inside, and the children’s books are under your nose. Last year, children’s books were the fastest growing section of the books market.

Yet the amount of space given over to children’s fiction and literature in the forums — newspapers and arts programmes — where we talk about books is remarkably small. We brood endlessly over Bookerish novels; when it comes to children’s, however, the genre is generally lumped together in a round-up a couple of times a year in a bid to help out grandparents buy something suitable. The most dispiriting result of that quest for Christmas and birthday presents is the gift book, a handsomely bound, expensive, finely illustrated thing, preferably a classic, that no child will actually read. The other problem is that there isn’t now any equivalent among publishers to Puffin Books in its golden age in the 1970s under Kaye Webb, when the imprint itself conveyed confidence; now the good stuff is patchily spread.

What’s more, a lot of new books for children are shamelessly derivative. I’ve just started one where the prelude is pure Harry Potter. Publishers have adopted the Amazon approach: ‘If you liked X, you’ll love this.’ Or, ‘For fans of Y’. In this overstuffed, over-formulaic market, there may well be a grateful readership for The Oxford Companion to Children’s Literature among, I suppose, school librarians and the like. Actually, what it’s really useful for is finding out what other works were written by the authors you like, and in browsing for that purpose you’ll come across entries that provoke interest, which is more than can be said for Wikipedia.

It’s a revision of the original Companion by Humphrey Carpenter and Mari Prichard, published in 1984 (available now from that enemy of the book trade, Amazon, for under three quid). It cuts back some of their entries and supplements them with contemporary ones. The original Companion made no bones of the fact that inclusion was not a judgment of literary merit; if a book made enough of an impact, in it went. The same is true of Daniel Hahn’s new edition. The trouble is, given the speed with which children’s authors come and go, it’s difficult to establish which fleeting phenomenon is going to cut it in the long term, at least until the next edition. By and large, Hahn includes most interesting contemporary talent, almost all of it British, though he is sparing on the value judgments and observations about technique.

So there’s space for Rick Riordan, for instance, whose anarchic American teen take on the Greek myths (the Egyptian series is less good) has done more for understanding Olympus than Mary Beard; ditto Philip Reeve’s extraordinary dystopian fantasies; ditto Katherine Rundell’s lovely Rooftoppers, though, oddly, not Gill Lewis. More often than not, the entries are merely descriptive, but occasionally Hahn breaks into more effusive prose — David Almond’s Skellig is ‘extraordinary’ (yep) and the lengthy entry on Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials trilogy is fulsome, even though some parts of the final volume are pretty well unreadable.

But that’s fair enough. The earlier Companion was more liberal in its judgments on merit and quite often got things wrong: it was dusty, for instance, about Lucy M. Boston’s character-drawing in the captivating Green Knowe books, dismissive of Elizabeth Goudge’s wonderful Little White Horse, terse about Molesworth and surprisingly grudging about John Masefield’s Box of Delights, possibly (along with The Hobbit) the perfect children’s book — were it not for the ending.

There are some new entries too, to take account of changes in social outlook; so where the old Companion had an entry on sexism in children’s books, the new has one on sexuality —viz, how gay characters are represented. And there’s a section on vampires.

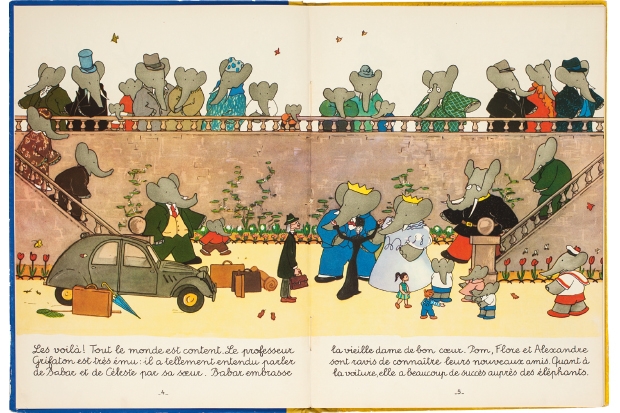

The most egregious change is that there are no illustrations at all but lots of entries on illustrators. This is probably for reasons of space, but the omission says a lot about our want of respect for a thriving form (though only for under-eights, alas). I mean, has anyone done more to contribute to the sum of human happiness than Quentin Blake? As Alice says, what is the use of a book without pictures? While Hahn is complimentary about some brilliant contemporary illustrators, like the sublime Jon Klassen (if you haven’t seen This is Not My Hat, go for it), the want of picturesis a real problem. Mind you, most literary critics are uneasy just talking about art in terms of style and technique.

On the bright side, the new version gives a couple of translators their due, notably the fabulous Anthea Bell, who carried off the extraordinary feat of making Asterix as funny in English as in French.

But back to the question of who would read a companion to children’s literature, which in turn raises the basic question of who reads children’s books. Just children? That was best answered by C.S. Lewis, who observed that just because he liked drinking port it didn’t mean to say that he no longer liked lemon squash. The two things are good, each in its own way, and putting away childish things when you grow up doesn’t include books written for children (people were very snooty about grown ups who liked Harry Potter). The Wind in the Willows is, to my mind, perfect English prose; lately I’ve been reading an unsettling book by Mary Norton (of Bedknobs and Broomsticks fame), called Are All the Giants Dead?, in the bath.

So, a companion to the genre is welcome. But its apparent authority is illusory. There’s no substitute, I’m afraid, for simply browsing books for yourself.

Available from the Spectator Bookshop, £25 Tel: 08430 600033

Comments