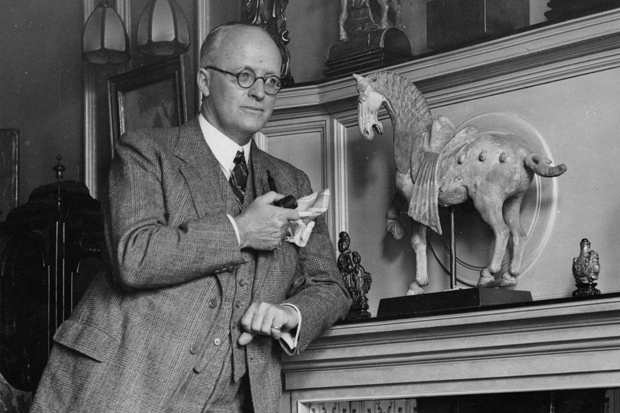

Hugh Walpole, now almost forgotten, was a literary giant. Descended from the younger brother of the 18th-century prime minister Robert Walpole, he was a prodigiously fast writer who seldom revised his work, producing at least a book a year between 1909 and his death in 1941. But who reads him these days? His books sold in vast numbers, including in America, where on his lecture tours in the 1920s he was more lionised than Dickens had been 80 years earlier. With his accumulated wealth he became a discerning art collector and left a fabulous legacy of paintings to the Tate and the Fitzwilliam.

In 1924 he made a home in his beloved Keswick, where between 1927 and 1932 he wrote the only one of his works which remains in print: this brilliant chronicle of the Herries family — the name Herries taken from Redgauntlet, the historical novel of Walpole’s literary god, Sir Walter Scott. Beginning in the early 18th century with Rogue Herries, the chronicle drives on through Judith Paris, The Fortress and Vanessa up to Wapole’s present day in the early 1930s. And what a saga it is!

The 3,000 pages of the four volumes seethe with drama, intense passions both thwarted and slaked, hatreds, feuds and disasters, as the lives of the descendants of Francis Herries, the original Rogue who sold his mistress at Keswick fair, play out against an unfailingly authentic historical background.

In recording every word of this gigantic saga, Peter Joyce took on a huge challenge, although for a man who has recently recorded Hamlet, playing every part himself, perhaps it seemed less daunting. Over two years Joyce spent 300 hours in the studio to record these 100 hours of the Chronicles’ four volumes, in addition to time taken to prepare the 3,000 pages for reading aloud. The result is extraordinary: an exceptional listening experience. A writer well overdue for a revival has been rescued.

Joyce doesn’t just read: he creates and extends Walpole’s magnificent theatre. There’s the ‘foul, baying rabble’ stoning Mrs Wilson for a witch before trussing her up and tossing her into the river, and the enraged Rogue Herries plunging in and cradling the limp ‘bundle of flesh’ he has rescued. There’s the fire which rips through Fell House and kills Adam Paris amidst the crashing roof and the trampling of the terrified horses, and crippled Uhland Herries killing his gentle, able-bodied cousin whom his wicked father Walter had taught him to hate. Joyce gives all Walpole’s drama an indelible extra dimension.

Joyce tempers his voice not merely to produce a vast panoply of emotions, but also to convey the maturing of a character. Judith Paris, found as a newborn baby beside her dead mother, the wild gypsy Mirabell, bows out of the Chronicles after her 100th birthday. The tempestuous Judith marries her childhood love, untameable Georges, who mistreats her; much later, surrounded by violent death in the Palais-Royal, she gives birth to an illegitimate son. Through all the vicissitudes of Judith’s life — and there are many more — Joyce retains her indomitable spirit, yet through his voice allows her to grow into a revered old lady in her bright shawls. To do this for more than 100 characters is a staggering feat indeed.

And then there are the many historical figures who step out from Walpole’s wide sphere of reference, their accents and voices meticulously researched by Joyce, such as Oscar Wilde’s prancing snappy tones and the strident Harriet Martineau, one of the ‘new militant women eager for her rights’. Joyce captures exactly the fey vulnerability of Coleridge’s elfin son Hartley, in complete contrast to the raw maleness of the champion boxers Heenan and Sayers. (Strong men, like David Herries who could carry an ox on one shoulder, appealed to Walpole.)

Times change from flickering candles, to gaslight, the Great Exhibition and electricity; horses give way to cars and experiments in flying; Judith’s clogs lined with straw are a curious memory amongst crinolines like cages; fox-hunting scenes on the wall are replaced by Japanese prints. But enduring and unchanging is Walpole’s passion, the ‘immortal ecstasy’ of the Lakeland landscape which is in the bones of all the generations of Herries.

Joyce succeeds in recreating with great sensitivity this fierce love of Walpole’s, in his constantly recurring descriptions of the light patterns on the lakes, or the shifting shades of saffron, rose, primrose, silver grey and black of the clouds and fell. It is here that Benjie, the last Herries of the chronicle, eventually at peace in his caravan beneath the Scafells, merges into the gathering grey, tended by John, his one true eternal friend — the sort of companion Hugh Walpole himself sought throughout his life.

Available from www.assembledstories.com, Tel: 01476 571333 or email sales@assembledstories.com

Comments