This has all the appearance of a book invented by a publisher. Two years ago W. Sydney Robinson published an excellent biography of the Victorian newspaperman W.T. Stead. How best to follow this? No attractive subject for another full-scale biography suggested itself. Why not therefore fill in time by writing long essays on four worthies from the generation that followed Stead? And so we have: ‘A Daring Reassessment of Four Twentieth Century Eccentrics: Sir William Joynson-Hicks, Dean Inge, Lord Reith and Sir Arthur Bryant.’ The only trouble is that the reassessment is not particularly daring and the characters hardly at all eccentric.

Joynson-Hicks — ‘Jix’ as he was usually referred to, and Lord Brentford as he eventually became — was bizarre rather than eccentric. All Robinson’s heroes were conservative with a small ‘c’ and usually with a large ‘C’ as well, but Jix was so far to the right that Robinson feels it necessary to protest that he would ‘likely have found Nazism as abhorrent and unchristian as he found Communism’. Jix defended Reginald Dyer’s handling of affairs at Amritsar, rejected partition in Ireland, violently opposed female suffrage and almost single-handedly defeated the move to introduce a revised Prayer Book. Even the most timorous steps towards reform were dismissed as being certainly socialistic, probably communist. D.H. Lawrence, whose Lady Chatterley’s Lover Jix did his best to suppress, denounced him as

one of the grey elderly ones belonging to the last century, the eunuch century, the century of the mealy-mouthed lie, the century that has tried to destroy humanity, the 19th century.

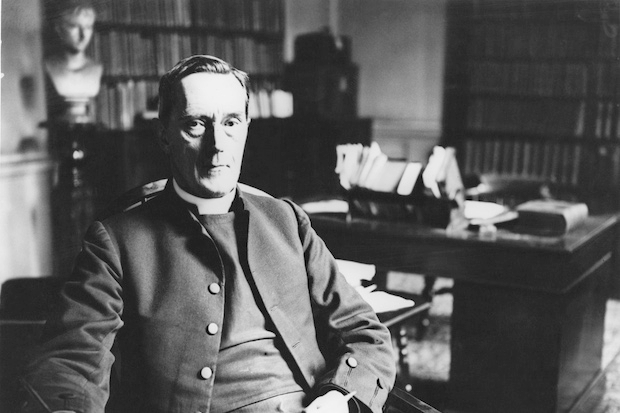

‘Mealy-mouthed’ is not a charge that could be brought against Robinson’s next subject, William Inge, Dean of St Paul’s, the ‘gloomy Dean’. Unlike Lawrence, Inge thought that the 19th century was ‘the most wonderful century in human history’ and denounced post-1918 England as ‘a chaos of factories and mean streets, reeking of smoke, millionaires, and paupers’. He was a pacifist and a francophobe who believed that Stalin was a greater blackguard than Hitler and that Britain would have behaved very much the same as Germany if it had been treated as badly at the end of the first world war.

Robinson clearly deplores Joynson-Hicks and Dean Inge, but his real venom is reserved for his third subject, Lord Reith. Reith was ‘restless, selfish, ambitious’, a man of startling arrogance who, when offered a knighthood, considered it almost an insult and remarked that the Order of the Garter ‘would not have been too much for what I have done’. What he had done was to build up the BBC from nothing into the most respected and powerful broadcasting company in the world. It was an astonishing achievement, and one which his manifold weaknesses might diminish but not destroy.

The historian Arthur Bryant was quite as far to the right as any of his companions. Unlike the others, though, who do not seem to have noticed that they were out of touch with their times, Bryant drew satisfaction from the fact that he was in many ways a 19th-century figure. He wrote in 1954:

It often amuses me, living in a seemingly different world — the world of the atom bomb, the aeroplane, television, parlour games, boogie-woogie and the strip cartoon — to find… that I believe in very much the same things as Queen Victoria and Lord Tennyson and Mr Gladstone.

Most diehards start with at least some slight pretensions to liberalism and only move gradually towards their entrenched position on the right. Bryant began as he meant to go on. ‘My essays were deemed dangerously reactionary,’ he wrote proudly of his days at Oxford. He still ended up with a First, though, and, since he wrote uncommonly well and vividly, he soon established himself as the best-selling historian since Macaulay. G.M. Trevelyan saw him (or at least told Bryant that he saw him) as ‘the coming historian. You will hold an important place as interpreter of the country’s history to the new generation.’ Most other professional historians were less generous: their — justified — conviction that they knew much more about their subject than Bryant did exacerbated their resentment at the fact that he sold 100 times more copies than they could hope to do. Most of his books are out of print today, but his immense readability makes it seem likely that they will survive into future generations.

Robinson says in his introduction that, as a schoolboy, he rejected the idea that the Victorians perished with the death of Queen Victoria and resolved to find ‘one of these living fossils’, a real-life Victorian. Sure enough, they lived on, he found, ‘in places as various as Pall Mall clubs, dreary seaside cottages and chilly, unloved tenement blocks, emerging every so often to denounce the slide in manners and morals since their parents’ day’.

His own protagonists (to call them ‘heroes’ would beg a lot of questions) are drawn from the middle to upper-middle classes. They are all intelligent, ambitious and rejoicing at the prominent role they play in public life. They can, therefore, hardly be described as ‘typical’ Victorians, if such an animal exists. Robinson acknowledges the inspiration provided by Lytton Strachey’s Eminent Victorians and ‘Not-quite-so-eminent-post-Victorians’ would provide an accurate if un-euphonic title for this book. It hardly achieves Robinson’s aim of ‘giving a portrait of an age’ but it is scrupulously researched, intelligent and uncommonly well-written. Robinson has real talent and I hope that he has by now found himself a more substantial subject into which he can sink his teeth.

Comments