With two new biographies of Kim Philby out, an espionage drama by Sir David Hare on BBC2, and the recent revelation that the aristocrat superspy John Bingham was the model for George Smiley, there is little doubt that Britain is currently going through one of its fitful bouts of spy fever, and this book can only add to the excitement.

Philby has a walk-on role in Jason Webster’s gripping and stylish new account of the extraordinary career of Juan Pujol, aka Agent Garbo — and a multiplicity of other monikers — arguably the second world war’s most successful double agent apart from Philby himself.

Pujol first crossed British Intelligence radar when the clever boys and girls at Bletchley Park codebreaking centre noticed signals from a new German agent, code-named ‘Arabel’, who claimed to be operating inside Britain. Arabel’s reports, however — including the important information that Glasgow shipworkers relaxed of an evening over fine wines — made clear that his information came from a fertile imagination.

Philby and other counter-intelligence officers quickly realised two things: that the Germans were apparently swallowing even the most absurd of Arabel’s inventions, and that if he were rumbled the whole British Double Cross system for turning and controlling captured German spies would be blown wide open. Arabel had to be found, stopped and turned in his turn.

They soon found that Arabel/Pujol had already been beating on British embassy doors in his native Spain and Portugal, begging to be allowed to spy for London, only to be turned away. But as soon as MI5 discovered his identity, Pujol was flown to Britain and put to work manufacturing a small army of totally fictitious sub-agents, all feeding false and misleading information to Pujol’s Abwehr controllers in Iberia.

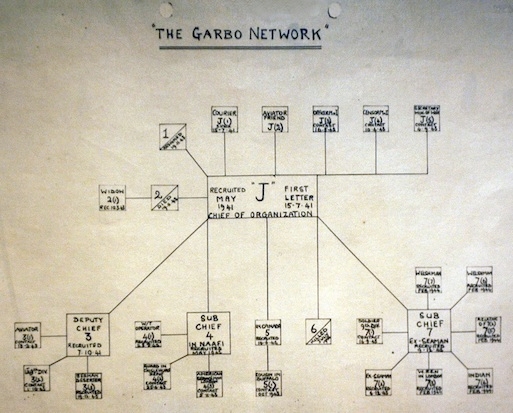

MI5 gave him the code name ‘Garbo’ because of his evident acting ability, and his imaginary network of agents also were baptised with a host of names reflecting their supposed status and occupations, including ‘Stanley the Welsh nationalist’; ‘Rags the Indian poet’; Fred the Gibraltarian; ‘the Widow’, the ‘Mistress’, and the refreshingly honest ‘Low Grade Spy’. It is a mystery how Pujol kept track of all his creations.

He was born in 1912 into a prosperous Barcelona family. When civil war engulfed Spain in 1936, his father’s dyeing factory was expropriated and his family imprisoned by the Republicans. Pujol joined their army in order to desert to the Nationalists, but he was treated just as badly by Franco’s victorious rebels, giving him an enduring hatred of both communism and fascism.

When the second world war broke out, Pujol decided to become a spy to aid Britain, the only country resisting the Nazis. After being rebuffed by the British embassy in Madrid, he travelled to Lisbon, and set up as a freelance agent, ingratiating himself with the Germans, only to deceive them.

After finally setting up his spy shop in Britain under his Anglo-Spanish MI5 controller Tomas Harris (himself subsequently suspected as one of the Philby-Blunt Soviet spy ring) Pujol became the key agent in ‘Operation Fortitude’ — a series of elaborate deceptions designed to convince the Germans that the coming Allied invasion of occupied Europe would happen anywhere apart from its true target.

Pujol’s major contribution to Fortitude was to place his team of imaginary agents — the ‘29 names’ of this book’s title — in a variety of geographical locations and walks of life, supplying pieces of the Fortitude jigsaw designed to draw German attention and resources away from Normandy.

Fortitude succeeded spectacularly. On Hitler’s orders, German divisions — including vital armour — were kept back in the Calais area guarding against a cross-Channel invasion that never came. Meanwhile, the real invasion, regarded by Hitler as a feint, went ahead in Normandy against much weaker opposition as a direct result of Pujol’s work. Few spies make such a difference to history.

On 20 July 1944, nearly two months after D-Day, the Germans trustingly awarded their star agent the Iron Cross and $350,000 in cash in recognition of his valuable work. So why did the Germans swallow the garbage Garbo was feeding them? Webster believes that his controller Karl-Erich Kuhlenthal, a partly Jewish protégé of the disgraced Abwehr chief, Admiral Canaris, may have suspected that Pujol was a fraud, but guarded his own back by telling the Führer just what he wanted to hear.

After the war, Pujol, fearing German vengeance, emigrated to South American obscurity, only emerging in 1984 to receive an MBE from Prince Philip, and revisit the D-Day beaches he had helped to make so much less bloody. He died peacefully in 1988.

Pujol’s story has been told before, but never in such detail. When he’s not writing history, Jason Webster is a crime novelist, and this book reads like a thrilling work of fiction which (given that Pujol’s aliases were all fictional) in a sense it is.

Comments