There should be a sign on the door. ‘Plotless play in progress.’ Moon on a Rainbow Shawl, by Errol John, won first prize in a 1957 scriptwriting competition organised by Kenneth Tynan and judged by Alec Guinness, Peter Ustinov, Peter Hall and others. The West End promoters thought the script uncommercial and never gave it a decent shot at success. They had a point. Errol John, an apprentice writer, hadn’t learnt how to shape his tale for the theatre and give it that insistent rat-a-tat-tat rhythm of twists and surprises that audiences expect.

His languid drama is set in a Trinidad ghetto where a crew of washouts and wanna-bes bicker and copulate their way through a few steamy midsummer days. The grinding poverty seems quaint, and even attractive, to modern eyes. The sun shines. The rum flows. The local tarts are cheap and friendly. Fruit drops from the trees. The Caribbean leaps with juicy, fresh-caught fish. Work is plentiful. And eager souls can supplement their wages by strumming a guitar in night-clubs filled to overflowing with ever-generous Americans. But as I watched this torpid snooze-in something weird happened. I got interested. Then I got hooked. By the end, I was desperate to know what the characters would do next. It’s like the first episode of some off-beat TV drama. Once you surrender to its slow-march rhythm you’ll find its unfussy intricacies entirely captivating.

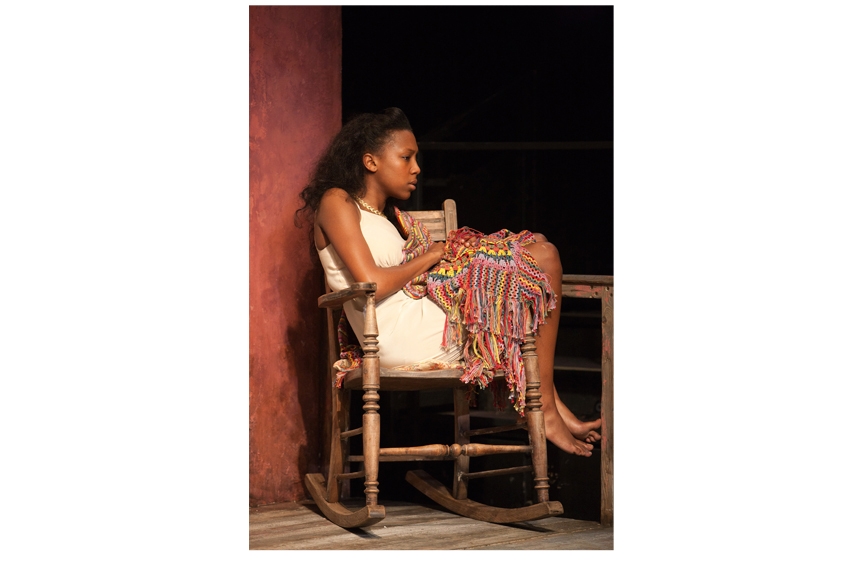

The central dilemma involves Rosa, a pregnant teenage bombshell, torn between two unsuitable suitors. Ephraim is poor, young, handsome and feckless. Old Mack is ugly, earnest and past it. And he keeps ‘plumping her up’ like a hotel maid doing the pillows. But he’s rich too. So no prizes for guessing which she chooses. The show’s best moments come from Jenny Jules, as a viper-tongued harlot, who has to placate her puppyish fiancé while she works her way through the entire crew of a US frigate moored in the bay. Jules is great to look at and brims with catty charisma. She gets fantastic comic support from Ray Emmet Brown as the slick, over-dressed dupe who wants to ‘make an honest woman’ of the biggest slapper in the Caribbean.

This show is a rarity. A play that bores me for ten minutes will usually forfeit my interest entirely. This bored me for half an hour but I came out loving it.

At the Arts Theatre, a new play about the miners’ strike offers a timely chance to examine the end results, 27 years on. The bottom line, by my calculation, is as follows. The strike was a victory for women. It ended the bigoted, male-dominated ethos of the mining communities and rescued them from the sad, hard-drinking, Neanderthal culture of pit life. Out went the filthy, dangerous business of scrabbling for coal underground. In its place came hi-tech light industries that favoured female employees and rewarded their reliability, flexibility, diligence and sobriety. That’s the audit for 1984/85. The closures dethroned men and handed the jobs, the cash and the moral authority to women. It was an internal coup led by that closet suffragette, Margaret Thatcher.

But you won’t hear those views aired by any of the veterans these days because the strike now stands as the great working-class sob story. Every day, the fairy tales of oppression are being reinforced by new tribes of martyred prophets and songsters of despair. This play, by Karin Young, adds to the chorus of deprivation. Like most female liberators she’s determined to give her excellent cause a lousy name. She shows us three middle-aged Geordie women who reminisce and weep about the mid-1980s. They agree that life was dreadful in those days — because of that terrible, terrible strike — and yet it’s even worse now. Why? Because that terrible, terrible strike is over.

One of the women has a pretty daughter who plans to celebrate her wedding with a boob job. Inevitably, this scandalises the ageing feminists. Having fought for the young woman’s liberty, they refuse to accept that she is, by definition, free to use it at her own discretion. Freedom that requires a lifetime of grateful thraldom to one’s emancipator isn’t freedom. It’s slavery — plus being nagged.

This is a trite, blinkered and faintly depressing slice of bogus sentiment. Just occasionally the woe-worshipping tone is leavened with a hint of self-mockery: the feminists line up and parade a political slogan on idiot boards. ‘Defeated Women Will Never Be United.’ The words, like the show, are in the wrong place. The Awkward Squad will feel more at home once it quits London and heads up the A1. That, happily, is where it’s going next. It’ll tour the north for as long as loser-mania lasts there. Possibly for ever.

Comments