On this Friday 50 years ago, at 1.30 p.m., the house lights at the Odeon Leicester Square dimmed for the first public screening of a British movie called Victim. It carried an ‘X’ certificate, which to the fans of its star, Dirk Bogarde, seemed decidedly odd. His reputation as the idol, not just of the Rank Organisation’s flagship cinema but of all the country’s Odeons, had been based largely on performances as Dr Simon Sparrow and Sydney Carton, and in other undemanding fare.

The film’s release turned out to be a defining moment in the career of a great screen actor and a landmark in British cinema. For some, though, this efficient little black-and-white thriller helped to change the world.

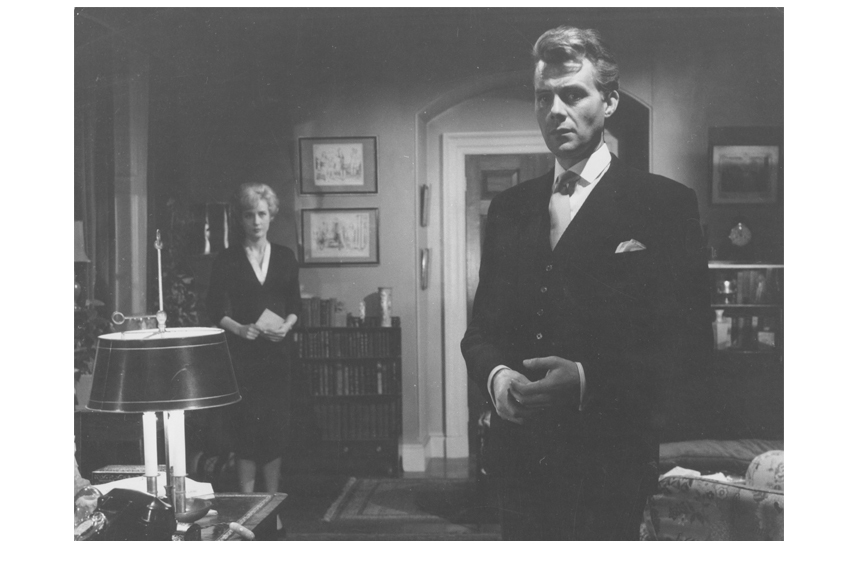

The plot involves the hunt for blackmailers who are targeting homosexuals. A young wages clerk, Jack Barrett, played by Peter McEnery, has been photographed, in tears, in a car driven by a successful barrister, Melville Farr (Bogarde). The nature of their relationship is less important than the fact that the lawyer is evidently compromised. As the pressure mounts on both men, confrontations take place between Farr and his wife Laura (Sylvia Syms) which to this day have lost none of their shock value and poignancy.

Beneath the basic story lies unashamed propaganda. When the film was shot, the ‘Government report into Homosexual Offences and Prostitution’, delivered to parliament by Sir John Wolfenden and his committee in late 1957, was stranded on the legislative rocks. Its principal recommendation — that homosexual acts in private between consenting adults should be decriminalised — had been, spasmodically, the subject of intense discussion; but for Westminster it was a reform too far.

Into the debate stepped the writer Janet Green, the producer Michael Relph and the director Basil Dearden. They had made Sapphire (1959), which used the detective-thriller format to plead for greater understanding in race relations in the wake of the Notting Hill riots of 1958. Now they were to espouse reform of a law, unchanged since 1885, that had become known as the ‘blackmailer’s charter’.

The film-makers consulted in depth with the Secretary to the British Board of Film Censors, John Trevelyan, whose liberal approach predisposed him towards their cause, but who was on highest alert to the ground-breaking theme and to its language. Despite many coy or ultra-flamboyant representations on screen, audiences had never heard the word ‘homosexual’ uttered on a soundtrack — not even in the two films then on general release about the misfortunes of Oscar Wilde.

By October 1960, four months after a Commons majority of 114 again put paid to any action on Wolfenden, Relph and Dearden had a viable script and turned their attention to casting. Several actresses declined to play the barrister’s wife, but, despite being five months pregnant, the enduringly feisty Sylvia Syms agreed. The central role of Mel was a hotter potato. Jack Hawkins withdrew at a late stage; James Mason and Stewart Granger were approached, but unavailable. Then Earl St John, executive producer at Pinewood, came up with a surprising suggestion: Dirk Bogarde.

At the time Bogarde was negotiating the end of his Rank contract. He was tired of being straitjacketed and, in his most recent film, The Singer Not the Song, had camped it up to a risible level as a Mexican bandit, sashaying about in leather and caressing a cat, largely as a protest against being cast opposite John Mills. When Dearden brought him the Victim script, it was manna from heaven.

There is a good deal of mythology about the atmosphere on the set, some of which would provide Bogarde with capital for his memoirs and public appearances in later years: how Dearden instructed the cast and crew not to refer to ‘pansies, poofs, nancies and faggots’ but, rather, as ‘inverts’; how a chippie broke the reverential ice by warning a colleague as the latter bent down: ‘Hey, Charlie, watch yer arse!’

Sylvia Syms remembers the entire operation as brisk, professional and unremarkable. But everyone recognised the importance of the subtext. She was involved in the film’s most powerful scene, largely scripted by Bogarde himself, when Laura challenges her husband about his real feelings for Barrett, and he replies: ‘All right, you want to know. I shall tell you. You won’t be content until you know, will you? Till you’ve ripped it out of me. I stopped seeing him because I wanted him. Do you understand. Because I wanted him.’

Such truthfulness and frankness both startled and reassured when the film went on release. If critics were divided as to its importance, audiences found it exciting and genuinely thought-provoking. The homosexual community responded with a sigh of appreciation. For the now-acclaimed director Terence Davies, then 15 and working as a clerk in a Liverpool shipping office, the screening of Victim at the local Odeon was a near-epiphany: ‘You could have heard a feather drop.’ The film had told him he was not alone.

It was another six years before parliament passed the Sexual Offences Act. Soon afterwards Bogarde received a letter from the eighth Earl of Arran, who had piloted the bill through the House of Lords. He had not seen Victim on its initial release, but finally caught up with it ‘on telly’. He told the actor how much he admired ‘your courage in undertaking this difficult and potentially damaging part’, then added that the swing in popular opinion favouring reform had been from 48 to 63 per cent. This, he understood, was in no small measure due to the film. ‘It is comforting to think,’ he concluded, ‘that perhaps a million men are no longer living in fear.’ Which, in itself, is a review in a million.

Victim, by John Coldstream, is published as a BFI Film Classic. A season marking the 90th anniversary of Dirk Bogarde’s birth runs at BFI Southbank until 22 September.

Comments