Prince Philip’s childhood was such that he had every right to be emotionally repressed and psychologically disturbed.

Prince Philip’s childhood was such that he had every right to be emotionally repressed and psychologically disturbed. Born sixth in line to the Greek throne, at the age of 18 months he was hounded from what, in name at least, was his homeland. His father came within an ace of being executed for high treason. When he was only eight his mother suffered a devastating nervous breakdown; in 1930 she was drugged into placidity, bundled into a car and consigned to a sanatorium-cum-prison. His father shrugged off his responsibilities towards his children, of whom Philip was by far the youngest, and installed himself with his mistress in the south of France. Philip was entrusted to relations in England, notably the Milford Havens, who treated him with kindness but never gave him the confidence to feel that he belonged. ‘When, years later,’ writes Philip Eade, ‘an interviewer asked him what language he spoke at home, his immediate retort was, “What do you mean — at home?”.’

Not only did he have no home, he had no homeland. In theory he was Greek, in practice German. His early education took place at an American school in Paris; he was then moved to an English preparatory school, followed by the rigours of Gordonstoun. By the time he was ready to begin a career he felt more English than anything, but he seemed as likely to join the Greek as the British Navy and, by the time war broke out, he was next in line to the Crown Prince to become King of Greece.

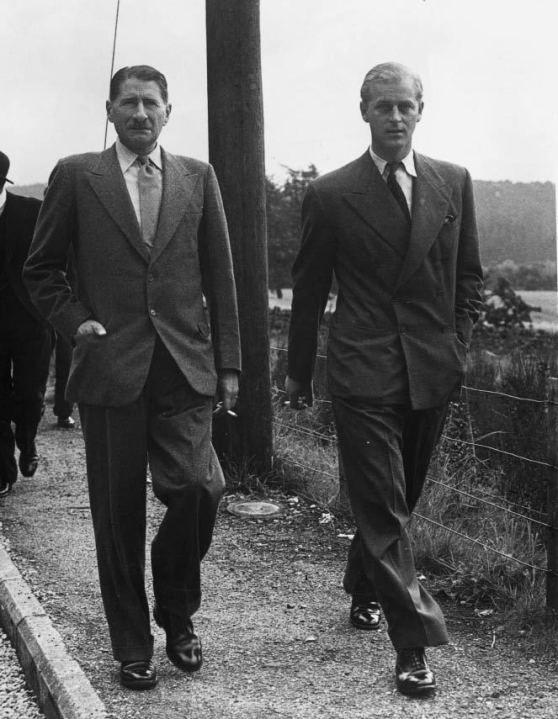

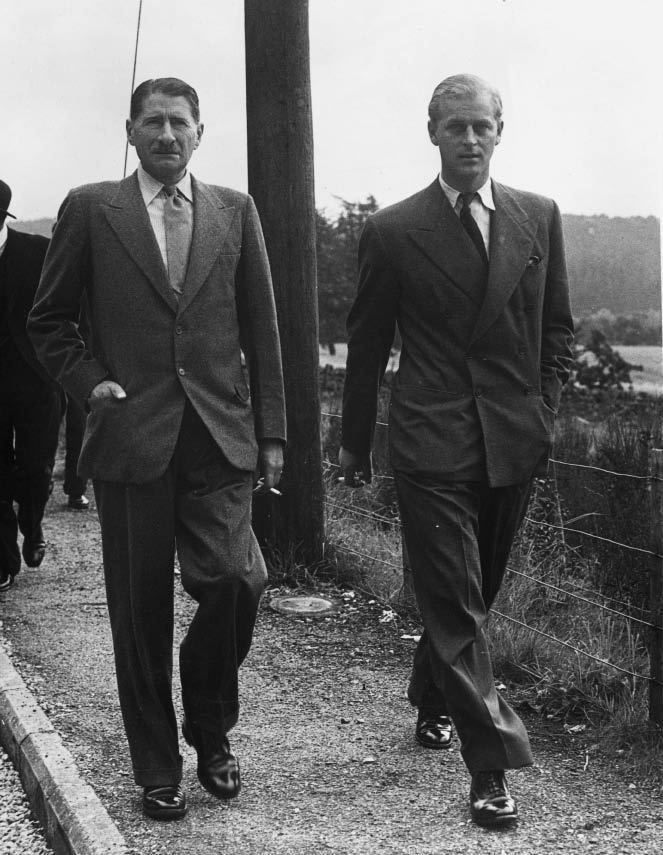

It was his uncle, Lord Mountbatten, who recognised the resilience and determination that enabled Philip to overcome the traumas of his youth, and who privately resolved that he would make a most suitable husband for the young Princess Elizabeth. It was he who ensured that Philip joined the British Navy, and in due course became a British citizen — a superfluous manoeuvre, since by the 1705 Act of Naturalisation of Princess Sophia he had enjoyed British citizenship from birth. Mountbatten himself was a suspect figure in the eyes of the stuffier elements of the British establishment; his championship of Philip reinforced the doubts of those courtiers who felt that Princess Elizabeth’s suitor came from the wrong country, had been to the wrong school and was indecently informal and disrespectful of hallowed traditions. ‘Lords Salisbury, Eldon and Stanley think him no gentleman,’ wrote the Queen’s first private secretary, Jock Colville, ‘and in a sense they are right.’ In another sense they were wrong. Philip was, indeed, uninhibited by traditional English upper-class shibboleths and cast a refreshingly acerbic eye on the atrophied rituals by which much of the machinery of monarchy was governed. He perhaps gave more offence than was necessary, but he was badly needed.

Eade describes sympathetically the stresses which the Prince’s role as consort cast upon him. By nature authoritative, brusque, disinclined to guard his tongue or take a back seat, he found himself doomed to a life in the shadows, always two paces behind his wife and Queen. He need not have taken on the role, of course, but equally he had reason to hope that he would not be thrust into it for another decade or more. Probably he would not have found his eventual fate any easier if he had been given ten more years as a successful naval officer. ‘Prince Philip was a highly talented seaman,’ said Lord Lewin. ‘If he hadn’t become what he did, he would have been First Sea Lord and not me.’

Abandoning his career might have been still more painful if he had risen higher in the naval hierarchy. As it was, he gritted his teeth, vowed to be Her Majesty’s ‘liegeman of life and limb’, and, with only a few minor slips and solecisms, has kept that oath with admirable fortitude to the present day.

But that is beyond the scope of the present book. Eade is the author of a well-researched and highly entertaining biography of Sylvia Brooke, the bizarre Ranee of Sarawak. Whether the early life of Prince Philip was really the right subject to engage his attentions is questionable. Perhaps this should be regarded as a sighting shot, staking a claim for the official biography which will eventually be commissioned. On the basis of this excellent book one can say that it would be a task that Eade was singularly well qualified to undertake; but one must hope that he will have to wait a long time before being given the chance.

Comments