A. N. Wilson has a queasy feeling that he won’t be re-reading the works of G. K. Chesterton for a while

Yet another book on Chesterton! William Oddie is only half way through his immensely detailed two-volume biographical-cum-theological study of the man mountain of Fleet Street. Last year we had Aidan Nichols on Chesterton’s theology. And now Ian Ker comes with the familiar account of how the son of a Kensington estate agent, educated at St Paul’s and infected with the spirit of the Nineties, moved from being a Bedford Park aesthete-agnostic, through socialism and liberalism to distributism, and from unbelief to a broad, generous sympathy with the Anglo-Catholicism of his wife, Frances Blogg.

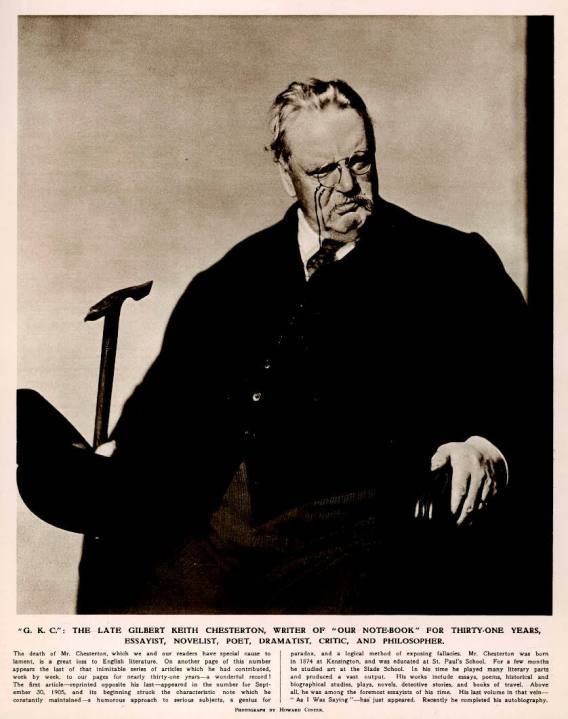

Then, in 1922, when Chesterton was in his late forties, he became a Roman Catholic. By then, he was a literary legend, immensely tall, hugely fat, never known to turn down a speaking engagement or a commission to dash off a book or an article. Slapdash but brilliant, the master of the paradox, he had become the defender of religious orthodoxy against the atheism of Wells and Shaw.

Ker’s book is immensely long, and it is full of details which Chestertonians will savour. Everyone knew that GK was fat, but I had never realised quite how fat he was until I read this book: he was scarcely able to get into the bath, and his wife had difficulty persuading him to wash. He never went to the dentist. And, although Ker tries to play this down, I had never fully appreciated before just how drunken GK became. Ker tells us that Frances would go to bed early and that GK sat up with the bottle, working.

This would certainly explain what must have puzzled many of Chesterton’s admirers, of whom I have always been one. How can it be that he writes such very good stuff beside such utter rot? When Chesterton is good, he is so very, very good. ‘Every citizen is a revolution. That is, he destroys, devours and adapts his environment to the extent of his own thought and conscience.’ Only he could have written that. Then you come across a sentence such as, ‘Gothic architecture … is the only fighting architecture’. What would that mean if it meant anything? But if we imagine that the author was drunk, then all is explained.

One piece of nonsense I had never come across before reading this book is Chesterton’s belief that the first world war was chiefly the responsibility of … who do you think? The German militarists? The Serbs? No. It was the ‘Quaker millionaires’. Asquith, it would seem, was afraid of alienating these pacifists, who were the main contributors to Liberal party funds. In consequence, ‘the Liberal Prime Minister did not make it clear that Britain would certainly intervene if France were threatened by Germany’.

There are so many things wrong with this cluster of errors that you wonder how anyone of Chesterton’s intelligence could have advanced such a crazy conspiracy theory. If it had not been for the Quakers, he wrote, millions would still be alive. It would be incomprehensible that any sane person could write this sober, but as soon as you see the bottle at GK’s elbow you understand.

Not that Ker — an ardent defender of Chesterton at every turn — would ever suggest that the works of the great master were composed when blotto. He merely gives us the evidence from which to draw such an inference.

Why is his book so long? Partly because he is as artless as it is possible for a narrator to be. Not for Ker to tell us simply that in 1921 Chesterton and his wife went on an American lecture tour. We have sentences such as: ‘On New Year’s Day 1921 the Chestertons left London’s Euston Station at 8.30 in the morning for Liverpool, where they arrived at 1.45 p.m.’ A biographer who is prepared to inflict this sort of information on the reader can fill up many pages.

Secondly, Ker gives long summaries of all Chesterton’s works, major or minor. And thirdly, he freely repeats himself. We hear twice, for example, an account of Chesterton acting in an amateur production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream, and of how genial GK was to the woman playing Puck, a Mrs Halford, who was Jewish. Big of him, wasn’t it? Because I love GK, I had never fully faced up, until reading Ker, to just how anti-Semitic he was. ‘Catholic internationalism, which bids men respect their national governments, is considerably less dangerous than the financial internationalism which may make a man betray his country.’ This is quoted with some approval by Ker, who does not provide us, as he perhaps should, with examples from English history of Jewish equivalents of Guy Fawkes.

Ker even half defends Chesterton’s suggestion that Lord Reading (Rufus Isaacs) should ‘ be dressed like an Arab to make it clear that he is a foreigner living in a foreign country’. Nor was I especially reassured by Ker’s sentence, ‘If we wince at the frequent references to “usurers”, knowing to whom Chesterton is referring, we should remind ourselves that he excoriated Prussians even more.’ Does this make it better? It reminded me of William Faulkner saying, sure he hated the Jews but what you had to remember was that he hated everyone else as well. Ker’s book comes with fulsome acknowledgements to Aidan Mackay, for a time the deputy chairman of the National Front.

By the time we reach 1928, GK has been RC for six years. When he went to see Mussolini, the Duce amazingly and amusingly wanted to quiz Chesterton about the revision of the Prayer Book in the Church of England. By now, alas, we feel that something rather sinister has happened to the Edwardian lefty GK we all loved. When that kindly minded distributist Maurice Ricketts resigned from the editorial board of GK’s Weekly because it did not sufficiently condemn the Italian invasion of Abyssinia, Ker thinks it is sufficient to remind readers that the staff and readers of the magazine were ‘even more divided over the Abyssinian crisis than over distributism itself’. Damn it, the Italians were bombing Ethiopian villages with poison gas! GK himself thought Fascism ‘no worse than a corrupt parliamentary system’. By then, surely, he has left all decent people behind.

If that is what GK thought, after a little over a decade in the RC church, then he had forgotten some of the lessons he learned when he was friends with the likes of Conrad Noel, the splendid vicar of Thaxted who conducted the wedding ceremony between GK and his wife Frances and who flew the red flag from his church tower and refused communion to employers who exploited their workers.

I had never thought, until reading Ker’s book, that Chesterton’s conversion to Roman Catholicism had made much difference to his essentially sunny imagination. Ker’s thoroughness exposes the mindset of his church during the 1920s and 1930s, and it is not especially edifying. You begin to see why T. S. Eliot found Chesterton’s ‘cheerfulness depressing. He appears less like a saint radiating spiritual vision than like a busman slapping himself on a frosty day’.

I shall always love Chesterton’s comic verse, especially his Old King Cole parodies, which are almost the only thing of his not quoted by Ker. I shall always love the Father Brown stories and The Man who was Thursday. But this prolix attempt to make Chesterton seem like an important thinker brings on the queasy feeling that I won’t be reading him again for a little while.

Comments