Blair Worden

J.R. Maddicott’s The Origins of the English Parliament 924–1327 (OUP, £30) is not one for the bedside, but its wide and profound scholarship has much to teach us about the roots and functions of an institution now subjected to so much unhistorical criticism.

Nicholas Phillipson’s Adam Smith: An Enlightened Life (Allen Lane, £25) is an absorbing and elegant account of Smith’s mind and of the Scottish context, social and intellectual, that produced it. D. R. Thorpe’s Supermac: The Life of Harold Macmillan (Chatto, £25) gives a wonderful sense of Macmillan’s complexity and stature and of the place of personality in the fortunes of power and the making of policy.

Marcus Berkmann

Every compulsive reader is on a quest of some sort, and mine, I have realised, is in search of the perfect comic novel. God knows why: I have 80-odd P. G. Wodehouses on my shelves, and a good quarter of those must be as near perfection as makes no difference. But the search must go on, even though out-and-out comic novels tend to sell modestly, excite little more than critical indifference and never win awards, Howard Jacobson’s recent gong notwithstanding. Especially do they never win the Bollinger-Everyman-Wodehouse Prize for comic writing, which by hallowed tradition, only goes to something deeply unamusing.

But this year I found a beauty: My Dirty Little Book of Stolen Time by Liz Jensen (Bloomsbury, £7.99). Jensen is Danish, lives in London and writes in English, and every book of hers is different. This one, which came out in 2006, tells the story of a sparky young house-cleaner and part-time prostitute in late 19th-century Copenhagen who, for reasons too complicated and daft to go into here, ends up in 21st-century London, where she falls in love. Time travel is not a fashionable subject for serious fiction, but the book has a wild energy, a narrative voice unlike any other, a plot of Wodehousian elegance, and great warmth of spirit. It’s also wonderfully, life-enhancingly funny, in both expected and unexpected ways.

Victoria Glendinning

The winner of the 2010 ‘Lost Booker’ prize, J. G. Farrell’s Troubles (Phoenix, £7.99), first published in 1970, seems even more marvellous second time round. Set in Ireland in 1919, where a shell-shocked major lands up in a rotting grand hotel dominated by relentlessly breeding semi-feral cats and mad old ladies, this is a merciless, tragi-comic take on the end of the Protestant ascendancy. It is one of Farrell’s ‘empire trilogy’, all now reissued, and is as good as The Siege of Krishnapur. Both are better than The Singapore Grip, which somehow fails to grip.

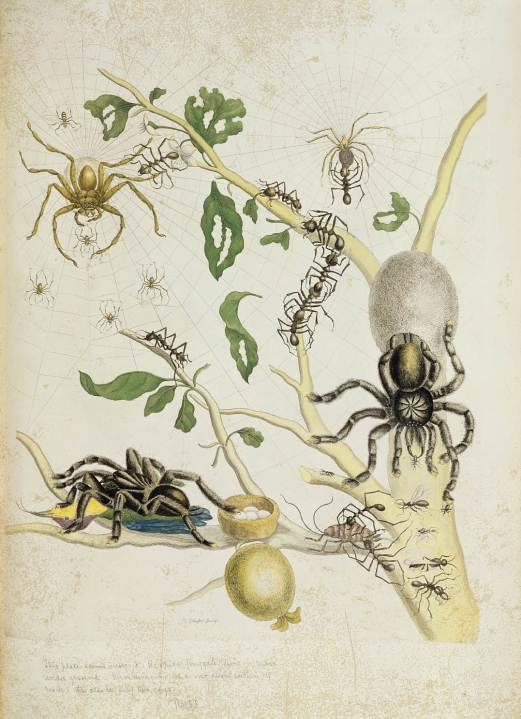

My other best book this year is Bugs Britannica by Peter Marren and Richard Mabey (Chatto, £35). It’s not only a scholarly reference work on insects and invertebrates, but an irresistible and somewhat eccentric compendium of brilliant images, observations and stories, to be dipped into and wondered over. I quixotically gave my copy away to a fellow pond-lover and beetle-watcher, and regret it bitterly.

John Preston

Norman Ollestad’s Crazy for the Storm (Harper Press, £12.99), is one of the best accounts of a father-son relationship I’ve ever read. Ollestad’s father was killed in 1979 when the plane he and his son were in crashed into a mountain in California. In part, the book is an account of the crash and its aftermath, but there’s a lot more to it than just another survival memoir. Ollestad also dissects a relationship between two people who essentially want to swap places, who each regard the other with mingled envy and awe.

Donald Sturrock is a first-time biographer, but his Storyteller: The Life of Roald Dahl (Harper Press, £25) is a tremendously assured piece of work. It’s plain that Sturrock admired Dahl — just as well, since the book is an authorised biography — but he never tries to gloss over his less attractive sides. Deftly, and with great acuity, he manages to embrace Dahl’s numerous contradictions.

Anita Brooker

Society is composed of two classes: the patrons and the patronised, and a change of status, the migration of the one to the other, is a subject well worth studying. Michel Houellebecq, misanthropist, Islamophobe, and rank outsider, performed this feat by being shortlisted for the Prix Goncourt, France’s most prestigious literary award. Houellebecq is famous for his preoccupations, which are largely rancorous, yet his novel La carte et le territoire (Flammarion) is mild, strangely addictive, but not without its subversive elements: Houellebecq himself features in it, ultimately as a headless corpse. Much of this is beyond parody. It is as if the author of Plateforme, by being favoured by the literary establishment, has reached new depths of anomie, yet there is a serious writer in there somewhere who has yet to do himself justice.

Far more engaging is Patrick Modiano’s L’Horizon (Gallimard). It deals with the impact of the past on the present, and the inescapable weight of memory. Two friends, who met originally in Berlin, come together again in Paris. They are now much older, yet time has done nothing to alter their strange alliance, which becomes increasingly more evanescent the more the author describes it, as if only the act of writing is stronger than the life it evokes. One is left with a strange anxiety, embedded in a style which is almost Parnassian in its calm.

I wanted to admire Jonathan Franzen’s Freedom (Fourth Estate, £20) but failed to do so — too many words, too many plots (not all of them credible) and inferior to The Corrections, which was a real tour de force. The effort involved in writing fiction can be onerous to the reader as well as to the author, and is all too palpable here.

The best book of the year was The Hare with Amber Eyes by Edmund de Waal (Chatto, £16.99), a memoir of the Ephrussi family of which the author is a descendent. Its subject, which is a collection of netsuke, sounds unpromising, but is in fact engrossing, and the extraordinary history of these tiny objects encompasses many changes of habitat. This is a memorable account, written with exemplary modesty.

It has been a poor year for fiction, though I enjoyed The Misogynist by Piers Paul Read (Bloomsbury, £16.99), again marked by a welcome understatement. Less really is more, as all these titles demonstrate in one way or another. Having said that, I return to Proust, a unique example of more being more, and never to be repeated.

Jane Ridley

The book trade may be in meltdown, but 2010 has been a bumper year for the reader. Candia McWilliam’s What to Look for in Winter (Cape, £16.99) is a masterpiece. It’s the autobiography of a woman who seemed to have everything. She was six foot tall and beautiful, she won the Vogue talent contest for young writers, she wrote prizewinning novels and married rich husbands — until blindness struck and her life fell apart. It’s wonderfully written (or rather dictated), with searing intelligence and the skill of a novelist at the top of her game.

Adam Sisman’s Hugh Trevor-Roper (Weidenfeld, £25), succeeds triumphantly in making the life of the arrogant don a riveting read. The petty vindictiveness of the Oxford historians, the high comedy of Trevor-Roper’s socially ambitious marriage to Lady Alexandra Haig, the tragedy of the history professor who was a cocksure journalist but failed to write the big book: all combine to form an irresistible story.

Gilbert Adair

The finest English-language novel I read this year was Nicholson Baker’s The Anthologist (Pocket Books, £7.99), a return to form for a writer who can sometimes be suffocatingly finicky and freakish but who, in this whimsical reverie on the sheer indispensability of poetry, a book which is itself possessed of the charm and sweetness of the most brilliant light verse, is some kind of a genius.

Patrick Buisson’s 1940-1945: Années érotiques (Albin Michel), an account of the erotic frisson prompted in Occupied France by the ubiquitous presence of youthful, muscular, flaxen-haired German soldiery (gentlemen, we discover, at least a certain type of gentlemen, really do prefer blonds) sounds like the sleaziest slice of pop history. It is, in fact, scholarly, fanatically researched and unexpectedly persuasive.

Cressida Connolly

Polly Samson’s new collection of short stories, Perfect Lives (Virago, £15.99) is terrific. Funny, beautifully observed and often poignant, they’re the best thing Samson has produced yet. Whether she’s recording the minutiae of modern marriage or the flora and fauna of a riverbank, this is a writer who misses nothing.

The Collected Stories of Lydia Davis (Hamish Hamilton, £20) was a revelation. The stories sound ghastly: some of them are less than a page long, few characters are given names and Davies approaches her subjects sideways and in sudden scuttles, crablike. But the effect is quite brilliant — wry, original and wholly unsettling. I can’t think of a book it would be more of a pleasure to be given.

Edmund de Waal’s The Hare With Amber Eyes (Chatto, £16.99) might have ended my marriage if my husband were not so infinitely long-suffering. There was no supper during the week I could not stop reading it, then for weeks afterwards I could talk of nothing else. It is simply enchanting.

Charlotte Moore

I revelled in David Kynaston’s Family Britain (Bloomsbury, £25) and am longing for the next instalment of this densely packed, non-judgmental social history of mid-20th-century Britain. Michael Frayn’s memoir My Father’s Fortune (Faber, £16.99) is exemplary; touching, funny, cleverly constructed and kind. I returned to Molly Keane’s Good Behaviour after 20 years and found it still perfect.

Clara Claiborne Park, who died in July, was an American academic. The Siege, her book about life with her autistic daughter, diagnosed at a time when psychiatrists blamed autism on ‘refrigerator mothers’, was one of the earliest parental accounts, and remains one of the best.

A. N. Wilson

Stuart Kelly’s Scott-land: The Man Who Invented a Nation (Polygon, £16.99) is a very engaging, highly intelligent conversation with its readers about what we owe to Walter Scott. His heritage is found not only in literature, but also in tourism, in the banking crisis (Kelly has some good things to say about The Letters of Malachi Malagrowther and their relevance to the crisis of 2008) and much more. The author is interested in everything, from Balmoral to the Wild West, from films to Hiawatha. I loved this book and heartily recommend it.

To coincide with the anniversary of Tolstoy’s death, Rosamund Bartlett has written Tolstoy: A Russian Life (Profile Books, £25). The extraordinary character of the giant is captured better by Bartlett than by any previous biographer, and this is partly because she knows Russia so well. Her description, for example, of the ‘Green Yuletide’ — Trinity Sunday — when Russians believed that the Holy Spirit descended on nature itself is unforgettable. She evokes the smell of cut grass and fragrant thyme at Yasnaya Polyana on that particular feast in 1877, when Tolstoy, still fervently Orthodox, was just on the point of lurching off on one of his religious adventures of total rebellion against the church. She is very good at expounding the novels and completely fair to all parties when the marriage turns into a battleground. Superbly well written.

Thirdly, is there room to say hoorah for Debo? Wait for Me! (John Murray, £20) by Deborah Devonshire is actually the one book this year that everyone will want in their Christmas stocking.

Philip Ziegler

After so many excellent biographies — those of Alistair Horne and Charles Williams in particular — it seemed that no further book about Harold Macmillan could be necessary. D. R. Thorpe proves one wrong in Supermac (Chatto, £25), an admirably fair and well-judged portrait of that most elusive of politicians.

Thorpe does full justice to the deviousness and sometimes unscrupulous opportunism which marked Macmillan’s career, but also conveys the charm, intelligence and, for the most part, wisdom that were so prominent in his personality. An exemplary political biography.

Jonathan Franzen’s Freedom (Fourth Estate, £20) may not be the great American novel but it is certainly a great American novel. One would hate to spend much time with any of the characters, but Franzen has an extraordinary gift for making them credible and for involving the reader in their activities. Freedom is enormously readable and totally convincing.

Bevis Hillier

‘I hate full-frontal flattery’, Candia McWilliam writes in What to Look For in Winter (Cape, £16.99). Well, sorry love, it’s my book of the year; and it’s not just a good book, but a great one. It is an autobiography interwoven with the miseries of suffering blepharospasm — a condition in which the eyes can still see, but the brain forbids the eyelids to open.

I remember feeling a bit envious of McWilliam. She was beautiful and brilliant, and in 1981 married the heir to an earldom (an option not open to me). I read her first novel, A Case of Knives, and thought it formidable, in the good sense. Some critics accused her of using too many long words — ‘she has swallowed the dictionary’ is a slur that still gets her goat. But for me the English language — like the library and the concubines of the younger Gordian in Gibbon — is there to be used. And if you don’t understand a word, you can jolly well look it up in the dictionary, which is also there to be used. I sympathise with her, as an over-zealous copyeditor cut out the words ‘flensing’ and ‘reddle’ (a dye) from my last book. We are treated to some rarities in her new book: ‘kenspeckle’, ‘scrobbling’, ‘epilimnion’ (the top surface of a large body of water).

The moment you begin reading this book, you are in communion with a starry intellect. And Candia McWilliam has the two essential attributes of a memoirist: ruthless honesty (for example about the alcoholism which nearly killed her, but is over now) and mastery of the language. Humour, too. Of the headmistress of her girls’ public school: ‘She would have made a wonderful-looking wife for a dictator.’ Of red tulips at Cortona: They preferred to be on flatter tilth [than black irises], as though they knew they were a motif on a million Turkish carpets’. The book ends in unqualified triumph: after an operation McWilliam can see.

I also enjoyed Adam Sisman’s Hugh Trevor-Roper (Weidenfeld, £25). The rivalry between the Regius Professor of History and A. J. P. Taylor is entertainingly detailed. In a television debate, Trevor-Roper addressed his adversary as ‘Taylor’; AJP called him ‘Hughie’. Sisman is level-headed about the searing debacle over the Hitler diaries. When Trevor-Roper was Master of Peterhouse, Cambridge, the dons who disliked him hissed, as he swept up to High Table, ‘Diariesssss!’. And the book yields one of the best puns ever: commenting on Tevor-Roper’s fondness for fox-hunting, the philosopher Gilbert Ryle said he was suffering from ‘Tallyhosis’.

Ferdinand Mount

Mark Girouard’s Elizabethan Architecture (Yale, £45) is a prodigy book devoted to the Prodigy Houses, those fantastical mega-palaces which reared up out of the placid landscape in the brief, dazzling period of Elizabeth’s ending and James’s beginning: Longleat, Hardwick, Burghley, Castle Ashby, Wollaton and Montacute. The English built nothing so breathtaking before or after. The illustrations are lovely, and so is the text: crisp, authoritative, with a touch of mischief. This is a ripe example of the Girouardesque, a glorious slab of a book. Si monumentum requiris, perlege.

Going to very cold places is the idealist’s last resort. David Vann’s losers escape into the snow and solitude without, of course, escaping themselves. In Legend of a Suicide (Penguin, £7.99), he strings together half-a-dozen stories of self-destruction (springing, partly at least, from the suicide of his own father). Vann brings the landscape of Alaska alive with a chilly glitter and accompanies the characters downhill with a sardonic attention to detail which makes you alternately want to weep and bark like a demented husky.Look out also for his forthcoming Caribou Island (Viking, £8.99) which carries on the grim work.

Comments