Even leaderless and without fresh ideas, Labour has surged in the polls. Think what the party might be able to do with someone – anyone – in charge

The Labour leadership contest has been easy to mock. It has set brother against brother, lasted for months and shown that the party has no heir to Blair. In private, Labour politicians are frank about the failings of their candidates. When I asked a senior backbencher about who he was endorsing, he replied, ‘The least worst one.’ Coalition ministers are gleeful about the weaknesses of the field. When I talked to one MP who is close to David Cameron about which of the Milibands he feared most, he laughed before dismissing them both with the jibe once deployed against William Hague — ‘weird, weird, weird’.

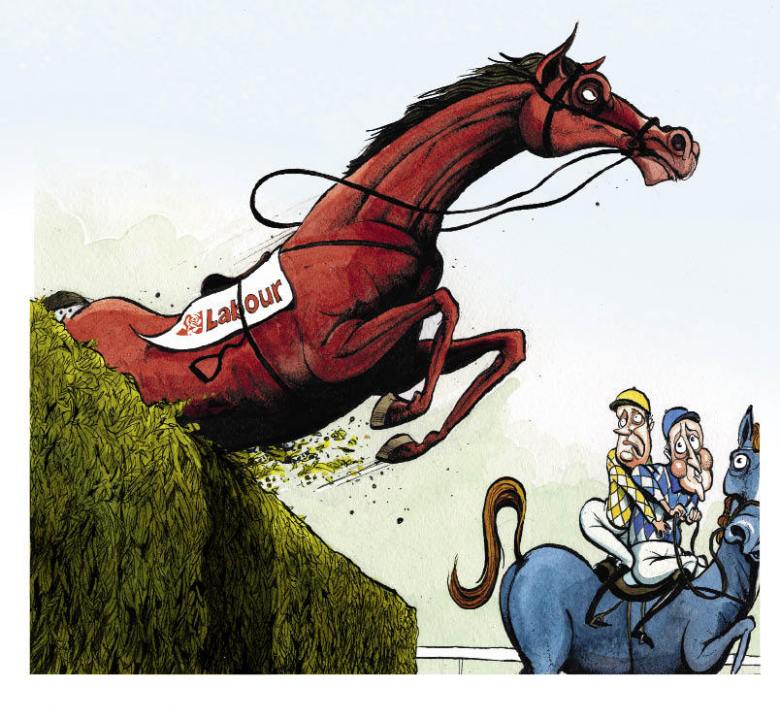

It is easy to dismiss Labour. Easy — but wrong. Not even the smuggest Tory MP could have failed to notice that last week the leaderless Labour party was neck-and-neck with the Conservatives in the opinion polls. Its core vote did not disintegrate in the election, and instead held firm enough to deny Cameron a majority. His is not a two-term mandate. So the perceived failings of the Milibands might not actually matter much. The new jockey may not be Frankie Dettori, but the Labour horse has more life in it than many think.

Far from being, as it is usually described, the worst job in politics, leader of the opposition might well be the easiest one over the next few years. Whichever Miliband is declared the winner this weekend may be carried straight into 10 Downing Street on the strength of anti-government votes. The new Labour leader will be heading a party that is the sole repository of anti-government sentiment at a time when the government is making £80 billion of spending cuts and introducing £30 billion of tax rises. Not since before the war has a fiscal consolidation of this scale been attempted. The millions who oppose it will have only one national party to turn to.

When the new Labour leader takes his place at the dispatch box, he will do so with 257 MPs behind him. It is a handsome number, a position which only three oppositions have failed to convert into victory since 1884. For all Mr Cameron’s skills, he is the most electorally unsuccessful Tory prime minister in history — that is why there are Liberal Democrats in the government.

Labour spent much of the election campaign in third place. Before the poll, it had adopted the brace position. Yet the party survived the election in remarkably good shape. Even though it fought a bad campaign — remember that appearance by the Elvis impersonator? — and was led by a leader who lost all three debates and publicly insulted an elderly voter in the final days of the campaign, its brand did not suffer the kind of damage that the Tory one did in the years up to 1997. Even on election day, Labour was judged the party most likely to have its ‘heart in the right place’. Voters had come to doubt Labour’s competence, but not its motivations. This gave its attacks potency. Even now, George Osborne believes that the televised leaders’ debates helped the Conservatives because they left Labour with less time to attack their planned cuts. People were still listening to what Labour was saying.

It is far easier to recover from a reputation of incompetence than it is to shake off one for being nasty. After 1997, the Tories did not draw level with Labour in an opinion poll for more than three years — and even then, it required the fuel protests to put them briefly in the lead. It took the Labour government three years to see its approval rating head to negative territory. This time, the government already has a net disapproval rating and Labour is already level-pegging with the Tories. With Gordon Brown gone, and the Lib Dems in government, a large number of voters have come home to Labour.

The Conservatives remain very easy to caricature; less than a quarter of voters think it is the party with its ‘heart in the right place’. This presents the new Labour leader with many targets of opportunity. It should be easy to persuade a suspicious electorate that the Tory cuts are callous and ideologically driven.

It is harder for Mr Osborne to argue that such cuts are vital, because fears of national bankruptcy have subsided (thanks principally to his decisive budget). This week, Moody’s said that the Chancellor’s cuts had saved Britain’s AAA debt rating. The news channels are no longer running a split screen with riots in Athens on one side and Westminster on the other.

So if the all-clear is being sounded, why the cuts? It is hard for the government to persuade voters that if there were not cuts, Britain would again be on the precipice. Labour’s case that they are vindictive and unnecessary is wrong — but easier to make. As Nick Clegg conceded in his conference speech, the deficit is now an ‘invisible crisis’. All of this amounts to the greatest welcome present that a new Labour leader could ask for. And this means that, from next week, the coalition government will have to change its game.

Cameron’s agenda is, as Margaret Thatcher’s official biographer observed recently, far more radical than hers in 1979. He is shrinking the state, taking on the teaching unions, reforming the NHS, and redrawing the welfare state simultaneously. He is doing this without the great advantage that Thatcher had, a divided opposition.

The Labour-SDP split divided Thatcher’s enemies and eased her task. Having only one national opposition party makes Cameron’s job harder. One Tory Cabinet minister recently told me that he feared Labour will be 15 points ahead by February regardless of who its leader is.

One of the great advantages that the new Labour leader will have is that the cuts will mobilise Labour’s stay-at-home voters. Of the five million votes that Labour lost while in government, only 2.6 million went to the Tories and the Liberal Democrats. A minority of the remaining 2.4 million went to minor parties but most of them just stayed at home on polling day. But Labour won’t have to strain to turn these voters out: the cuts will do the job for them. In 1997 Labour had a lead of 38 points among unskilled workers, the unemployed and those living on welfare. By the last election this had fallen to nine points. But it is hard to imagine that £80 billion worth of spending cuts won’t mobilise this section of the electorate.

Morale among Labour MPs is surprisingly high. Traditionally, the party disembowels itself after losing power — the tribes embark on a civil war, which tends to last for years. This time, they are holding things together. The failure to depose Gordon Brown may have cost dozens of seats (some argue it cost the election), but it has prevented the Blairite-Brownite feud passing down the generations. Labour has also not suffered the cull of its captains that the Conservatives did in 1997. Every Cabinet minister survived the election. There is no leadership contender who was prevented from making it to the starting gate by the electorate.

Those on the Labour side who wanted to go and make money, or just do something else, left the Commons before the election, when 100 Labour MPs stood down (a number swelled considerably by the expenses scandal). Those Labour ministers and members who objected in private to Harriet Harman’s plans to make it more difficult for MPs to have second jobs have quit. The new Labour leader will not have the problem that successive Tory opposition leaders did of half their team doing other, better-paid jobs at the same time as serving in the shadow cabinet.

Remaining Labour MPs are fighting with the ferocity of a regiment determined to recover its regimental colours from the enemy. Ed Balls has attacked Michael Gove again and again, inflicting blow after blow. While the ability of Labour and its allies to keep the story about Andy Coulson in the news day after day shows that it still knows how to run a media campaign.

Not everything in the Labour leader’s garden will be rosy. He will be up against David Cameron, a natural prime minister who looks the part and understands the role. His response to the Saville Inquiry demonstrated a Blair-like ability to shape and respond to the public mood. Tory and Lib Dem strategists believe this contrast is crucial, that neither of the Milibands can appear as credible prime ministers: David because he lacks the communications and personal skills that a modern prime minister needs, Ed because he is too far to the left, too far out of the mainstream.

Indeed, several Lib Dems told me at their conference in Liverpool that they believe that if Ed Miliband becomes Labour leader, they could replace Labour as the party of the centre. Many Tory MPs believe that Ed Miliband would cede aspiration and the middle classes to them and that David is just too intellectual to connect with Middle England.

But such complacency about the Milibands is ill-advised. David Miliband is no Blair or Cameron. But he is improving fast. The weird facial movements that made it so hard to take him seriously have gone, to be replaced by a more dignified countenance and a set of smart suits. His brother is certainly more left-wing. But, as one wise Tory remarked to me, he has an ability to make left-wing views ‘sound more reasonable than they are’. He’s no Michael Foot, or even a Neil Kinnock.

The Labour leader’s first 100 days will be crucial. The coalition will need to destroy him early on — and they have every intention of so doing. One Tory strategist even told me that he thought the coalition was in deep trouble if the new Labour leader makes it to the New Year as a credible figure.

We have seen, as Michael Ashcroft laments in his campaign review, that Labour is far better at attack than the Conservatives or Lib Dems are at defence. Last week, Danny Alexander was asked in front of a BBC radio audience if he was prepared to let thousands of public sector workers go on the dole. He waffled, to shouts of ‘Answer!’ It was a reminder of how ministers still struggle to articulate the need for cuts.

It is, of course, the new Labour leader that should have problems. Its borrow-and-spend approach would exacerbate the country’s economics problems and impose an ever greater debt on future generations. Tackling the deficit keeps interest rates low, and borrowing cheap. Free schools and the pupil premiums will reduce educational inequality. Welfare reform will remedy the evils of the dependency culture. To oppose all this should be a source of embarrassment — but not if the terms of the public debate have not been turned.

The coalition’s schadenfreude may soon give way to fear. It will take time for its economic and public services reform programmes to bear fruit. Winning the argument is always hard for those advocating radical reform and especially so if things get worse before they get better. This is what will provide Labour with its opportunity.

The coalition cannot afford to be complacent about the threat that the opposition poses to it. It mustn’t slip on a Miliband banana skin.

Comments