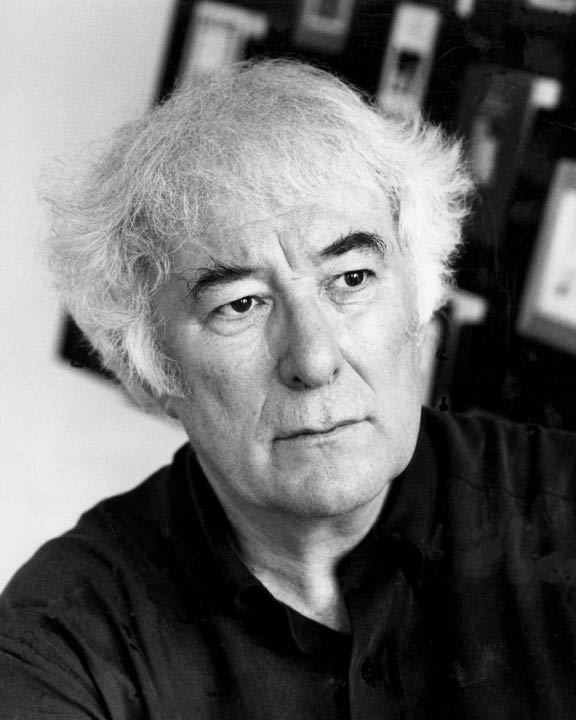

Among the most famous of all living poets, Nobel Laureate, highly educated, revered for his lectures and ideas as well as for his poetry, Seamus Heaney has a daunting reputation. He remains, however, enjoyed by a broad spectrum of readers, accessible, song-like, direct, concerned with everyday details and human relationships. Essentially, Heaney’s poetry strikes to the heart through its central metaphor — the very mechanics of being human.

Human Chain, his latest collection, makes this familiar territory absolutely explicit, right from the title. Not only does the image of a ‘chain’ of being human concern itself with family loyalties, connections and inheritances, but it also represents the physical labour of sharing a heavy load, completing a painful task, moving the weight of each other down the line, from a child lifting his face to see a kite break free of its string, to the awkward lifts, hoists and straps used for the injured and the elderly, to the image of the title poem where a line of aid workers and soldiers swinging sacks of grain triggers the poet’s empathy as a physical sensation in his back and hands, marking out at once the limitations of the human frame and the spiritual connection that can move beyond those limits.

In ‘Miracle’ the human chain is made of ‘those who had known him all along’ who carry the man on the stretcher to be healed. It is their story here, the story of their physical discomfort, the pain in their shoulders, the ‘ache and stoop deeplocked / In their backs’, the difficulty of their task, lifting him to the roof, strapping him tight for descent, the rope burn in their palms that is still stinging after the miraculous cure has taken place. The miracle is felt by these close observers as a physical thing, a ‘slight lightheadedness and incredulity’ that is intimately connected to the resilience and sweat that went into achieving it. The Biblical story underpins the image of humans as levers, hoists, props, each other’s limits and each other’s best support.

In the context of the previous sequence of hospital poems, ‘Chanson d’Aventure’, the man on the stretcher can be seen as the poet himself, ‘Strapped on, wheeled out, forklifted, locked/ In position’ in the ambulance, but ‘Miracle’ stands alone too, where the final lowering of the awkward weight must carry images of burial as well as resurrection.

The central section of the ‘Chanson’ charts the journey of the body as a repository of memory. Here the poet’s hand, paralysed and without sensation on the journey through the villages of his childhood to the hospital, contains nonetheless the memory of a bellrope and the knowledge of how to work it. The numb hand becomes the rope itself. If this is Heaney’s version of ‘for whom the bell tolls’, echoed in Larkin’s ‘Ambulances’ as the sirens visit every street, here it has become a moment of symbolic endurance, testament to love’s mysteries, written in the book of the mortal body, outliving sensation.

In the third section of the ‘Chanson’ trilogy, the simple trick of poetry is laid bare — the broken image of the Delphi charioteer, arms outstretched towards a point beyond the missing hands to the missing horses, overlays the image of the poet in physiotherapy, walking between parallel wooden bars, overlays in turn the memory of walking between plough handles, guided by another set of hands, alert to each slip, each stone jarring painfully through the wrists.

So the human chain passes on and re-learns essential skills of walking, ploughing, and perhaps too a belief in the kind of miracles won from the land and from hard work. The link that forges this simple image-chain is the stance itself, a man standing with his arms outstretched as if marking out the limits of the human frame.

Perhaps the most ambitious interweaving of the classical idea of human journeys with the particular, domestic and political of ‘home’, is the sequence ‘Route 110’ which begins with the poet buying a ‘used copy of Aeneid VI’ in a shop smelling of ‘dry rot and disinfectant’ and moving to and fro between the living and the dead along a path marked out by the familiar bus route, 110, ‘Cookstown via Toome and Magherafelt’, where the driver winds his passengers into life by cranking the list of names into the display panel, as if the talismans of their journeys really were a spell that wound the limbs of the dead into action. An image repeated at intervals throughout the book, of the empty coats and suits of the dead, are seen here on racks in the market, swaying together like ‘their owners’ shades close-packed on Charon’s barge.’

In ‘A Herbal’, inspired by Eugène Guillevic’s ‘L’ herbier de la Bretagne’ the human link is aural rather than visual, the poem answering the wish expressed in the second section for a sound recordist to ‘make a loop’ of the sound of feet through wet grass in a field through its repeated ‘sh’ in the opening stanzas, then the re-iteration of names of grasses, the bracken, broom, vetch, dock, rush clump, ‘sphagnum and buttercup’. By repetitions and echoes, its constant re-visiting of the grasses and sky and graves of the opening image, the poem becomes the answer to its own final question: where can we re-find a world where we fully belong? By carving one out of sounds here on the page, where sound and memory, living and dead are woven tightly together ‘like a nest/ Of crosshatched grass blades’.

Comments