If you are in the habit of reading short-story collections straight through you will not fail to notice the repetition of motifs in Ryan O’Neill’s playful debut. I’ve no doubt he would like you to, for his book is a set of variations on the theme of language.

We meet tattoo artists, English teachers, readers of comics, short-story writers, parents uttering racist epithets (‘Chink’, ‘Abo’ ‘Goon’), translators and a failed novelist called Thomas Hardie; there are also maps, mail-order books, pornographic magazines and changes of name. Even buildings have last words: a ten-year-old headline outside a derelict newsagent, the walls of which were ‘a palimpsest of graffiti’.

O’Neill is a Scots-Australian who spent two years teaching English in Rwanda. His repetitions are not restricted to English. Scotland, Australia and Rwanda all figure, the last most tellingly. Characters speak in a Babel of languages, among them Chinese, Lithuanian, Hungarian, Doric (the dialect of Aberdeenshire) and Kinyarwanda.

And then there are the recurring images and themes: of machetes and cockroaches, suicide and deception, divorcings and departures, red lorries and yellow lorries, all in some way demonstrating the power and dangerousness of words.

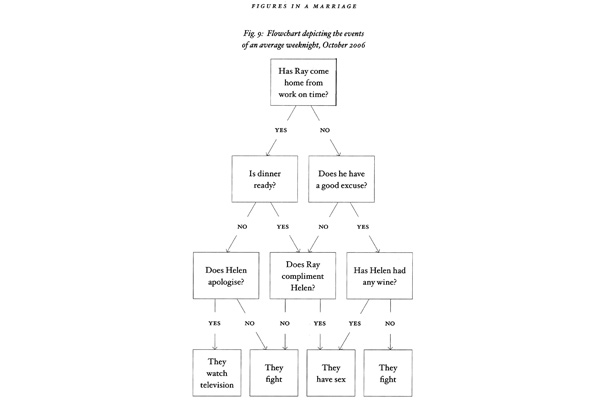

There are word searches, graphs, flowcharts (as above), tables of vocabulary, stories written as examination papers, as plans for a short story, as a book review and in terms of arcane literary devices such as calligram, peripeteia and epizeuxis, in footnotes, in different typographies and so on.

This is undoubtedly fun, and it is also clever, with a hint of the sense of being too clever by half, and if you read the book through from start to finish the tricks do begin to become tiresome. In fact the best story, by some distance, is the most orthodox. It has about it the ring of truth, of the imagination of the writer engaged not intellectually but in sympathy. It is called ‘The Cockroach’ and relates the escape of a ten- year-old Tutsi girl from the Hutu genocide in Rwanda.

O’Neill’s writing is generally crisp and clear and authoritative but marred by the occasional weighty simile that unbalances his sentences, like an anvil plonked on one end of a seesaw: ‘She always had an exhausted and agonised air, as if she had just been taken down from a cross.’

Perhaps the purpose here is to stop the reader in his tracks, and to invoke the sufferings of Christ, but the effect is at best baffling, and actually unintentionally comical: the reader can almost hear the writer thinking. In another story a crooked street is ‘like a life of virtue corrupted’, but then again it turns up in a first-person narrative, so perhaps O’Neill is not himself to blame and I am too dull to catch the nuance.

This is a clever, enjoyable, occasionally moving collection. For all the chicanery and the sense of a writer merely exercising considerable literary craft, there is an attractive softness hinted at in the title. One wonders what will follow next. It may be worth the wait.

Comments