There are two ways to see Rishi Sunak’s rescue package. One is an obviously needed and politically unavoidable boost to the economy and a relief for the cost-of-living crisis. The other is worrying jump towards the tax and spend policies that he once promised to avoid – and a sobering note for those who expected anything different from him. James Forsyth is inclined to the former, Kate Andrews and I are inclined to the latter. We all discuss in today’s Coffee House Shots podcast.

There are many ways a Tory government could have helped households this week. Fuel costs are soaring but about 25 per cent of all electricity bills are green taxes: why not cut them? What about making things better by not making things worse in the first place? Sunak jacked up National Insurance only last month, slicing a further 2.5 per cent from salaries – what David Cameron used to call ‘a thwacking great jobs tax’. Why not suspend (or abolish) that? But Sunak instead chose not only to keep the existing taxes but impose a windfall tax he used to argue against. He used the loot to increase handouts to favoured groups. A standard tactic: for Labour governments.

Listening to Sunak’s statement, I was struck by how much of the language could have been (and once was) used by Gordon Brown. There was talk about the ‘extraordinary profits’ that need to be nabbed by the state – a concept that is rarely heard from Conservatives who usually argue that competition is the remedy for firms who abuse any market dominance.

Sunak spoke about the ‘tight’ labour market but, as with the Brown years, no reference is made by Johnson’s Tories to the 5.3 million Brits kept on out-of-work benefits. They are in danger of being airbrushed out of the national conversation. The 5.3 million total is not even published by the government: the Spectator data team worked it out by mining the DWP database and we’ve added the below graph to our data hub. How can we ever have an economy firing on all cylinders while excluding 12 per cent of the working age population?

Listening to Sunak’s statement, I was struck by how much of the language was once used by Gordon Brown

It was five million under Brown, as well. And yes, the figure was increased by the pandemic. But we now have record vacancies and still a million extra people on out-of-work benefits, so something is clearly going badly wrong. It would be tragic if the Tories lose their interest in the supply of workers as well as supply-side economics.

In his speech, Sunak spoke about the energy price cap, another Labour idea copied by the Tories. The state cast as the provider, sweeping in to help those in distress. No mention of the fact that the state had compounded the distress in the first place by taxing salaries, fuel bills, petrol and more. Under Boris Johnson, the UK government is now 55 per cent bigger than it was in the Blair years: the sheer cost of maintaining this behemoth (taxes are now at a 72-year high) is a massive pressure on the cost of living. So the slide into Brownism isn’t just the policies, hitting a level of tax and spend that Brown never dared to aim for, but the prevailing language, attitudes and instincts.

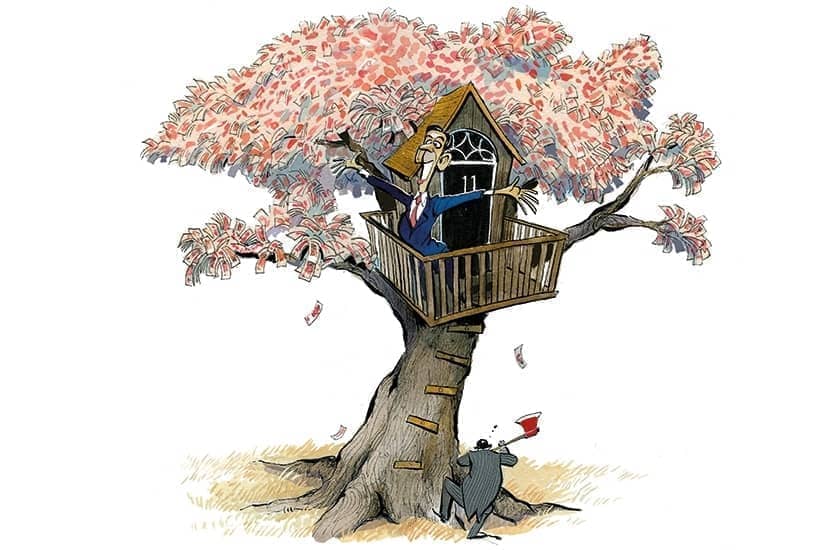

When asking around about what I perceived as a slide in Tory language and thinking, I picked up on Thursday’s Cabinet meeting where (I’m told) much of the chat could have been lifted from drinks in Brown’s No. 11. Sunak did not sound regretful about his windfall tax and spoke with enthusiasm, invoking Margaret Thatcher as if she was the patron saint of high-taxers. Oliver Dowden said the windfall tax was politically the ‘right thing to do’. Nadhim Zahawi asked why not go further: supermarket petrol retailers are making a killing, he said, and are not subject to the windfall tax. Those like Liz Truss, who had spoken out against this before, stayed quiet. The decision had been made.

The Prime Minister summed it up by saying the oil and gas companies obviously had no use for their money as they had been returning cash to shareholders, so why not just take it? All this is on top of the planned increase in corporation tax from 19 to 25 per cent. As Neil Kinnock might say: if you’re a company in Johnson’s Britain – especially an energy company – I warn you not to be successful.

Jacob Rees-Mogg, who spoke against the National Insurance rise, was the lone voice of dissent against the windfall tax. Which is not, actually, a one-off hit but a multiyear penalty. The rate of tax for North Sea companies rises to 65 per cent – and stays there until December 2025. So we clobber the sector like this, then expect them to innovate to produce more, cleaner energy and lower bills? Might the oil and gas sector be forgiven for thinking that, if they ever do succeed, the Tories will declare this ‘excess’ profits – and just raid them yet again?

This is supposed to be where Conservatives differ from Labour. The right argue that societies are fairer and stronger when people are trusted to keep more of the money they earn. This emphasises respect for liberty and a trust in people, families and communities.

I have tended to see Sunak as a principled politician caught in incredibly difficult circumstances. He inherited wild spending promises from a Prime Minister who was (until the Owen Paterson debacle) out of control. HS2, the science research bung, the ridiculous purchase of the collapsed OneWeb satellite scheme: he was in expansionary mood and took the view that with government (as with the redecoration of the No. 10 flat) you could spend now and then the money would sort itself out later. Sunak had to handle all of that, but in his last budget he told MPs that a line had been drawn. From now on, any extra marginal pound would be used to cut taxes: that was his future direction of travel.

But it’s harder, now, to see where Sunak is heading. He has chosen the bung over the tax cut, a hallmark of tax and spend Chancellors. If Chancellors are to be judged by deeds rather than words, Sunak is showing that he mistrusts the general public with tax cuts and prefers targeted welfare spending. He has become, however reluctantly, a high-tax Chancellor in a high-tax government. The below speaks for itself.

David Cameron and George Osborne would often say that they were hemmed in: they had no majority (and after 2015 only a tiny one) so lacked the political space to pursue liberal reforms that would have empowered ordinary people and rejuvenated growth. Boris Johnson won a landslide majority, yet at each turn feels the gravitational pull towards tax and spend policies and the economic worldview of the left. How is the economy expected to pull off any serious growth under the weight of these taxes – and a government that has far outgrown its usefulness?

Compare all European economies to where they were pre-pandemic – and where they’re expected to go next – and Britain is the second worst under a government that prioritises tax over growth.

The PM really should not be surprised if, when faced with two tax and spend parties in the next general election, voters go for the real thing.

Comments