Richard Batterham died last September at the age of 85. He had worked in his pottery in the village of Durweston near Blandford Forum in Dorset for 60 years continuously. It was, in its own way, an heroic life.

Batterham took an astonishingly pure, austere approach to his work. Quite simply, he undertook every part of the process of making himself. He made his own stoneware clay bodies, arguing that those who used bought-in clay missed out on the beginning of the whole process and were mistaken to think that they could just inject their artistry at a later stage.

He threw his pots on an archaic kick-wheel. He did not decorate them, save by working the clay itself by incision, flutings and chatterings, to shape the piece and catch and display the glaze. His exquisite ash and iron glazes in greens and greys he made himself too, arriving at them by a process of trial and error, always testing, adjusting, choosing.

Despite early recognition of the excellence of his work, he eschewed all self-promotion, keeping his prices modest, to make it available for use as well as display.

Batterham, in a way nobody else has ever quite done, made a tradition of himself

When he did speak about his work, it was in the briefest, most understated and practical terms only, as I found out when trying to interview him once. He liked to talk about the pots as though they evolved almost without his conscious participation, leaving him to look at them afterwards, select what worked best and take it forward. By this process of ceaseless refinement, his work achieved extraordinary subtlety, the smallest changes of form and glaze taking on significance in the unbroken series. For the most remarkable of his austerities was that, as well as focusing his life so certainly from an early age and simplifying his working practice so decisively, he chose to make a relatively small range of pots over and over again. Batterham, in a way nobody else has ever quite done, made a tradition of himself.

Not that his pots ever were the same. Each one, even in the domestic ware, is different, subtly but eloquently. Some sing more than others, Batterham would say. All, though, have a vitality that’s there in his very handling of the clay.

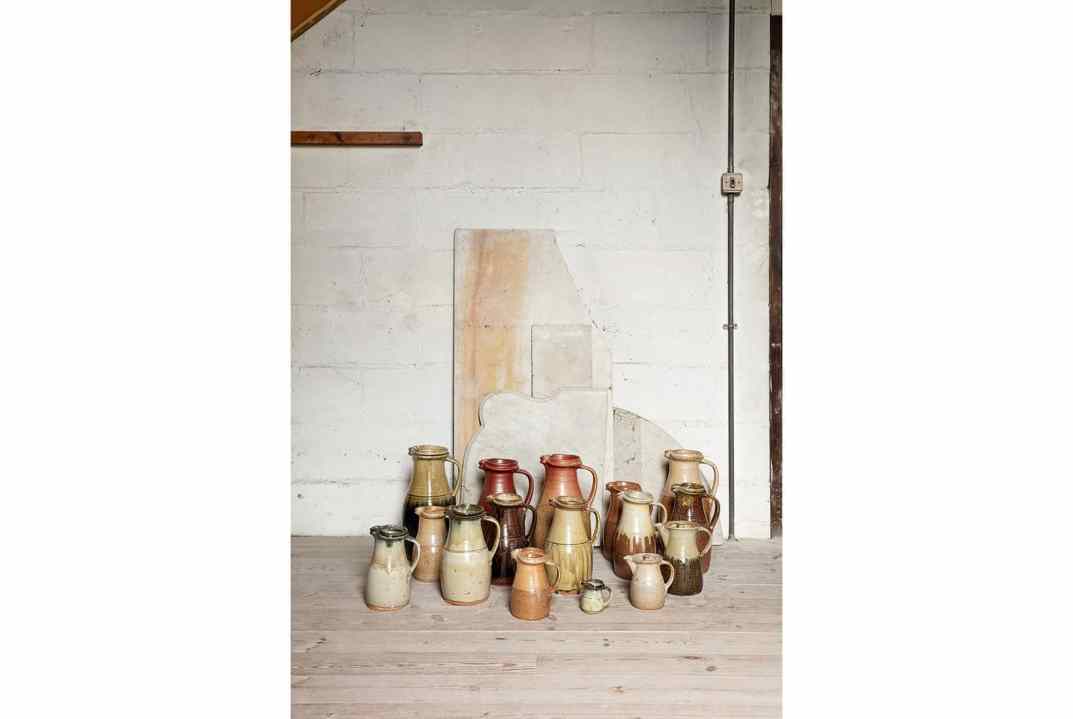

Throughout his career, Batterham kept back certain pots that he felt had something special about them, good or bad, as a reference for himself – and, after downing his tools, he collaborated on an exhibition of the good ones, supplemented by some of the pots he and his family used at home, a particularly appropriate undertaking given his approach to developing his work.

The show is exemplary. The spacious, light-filled Room 146 at the end of the Ceramics Galleries at the V&A, dedicated to Richard Batterham: Studio Potter, is one of the pleasures of London right now: the presence of these pots, so enjoyable singly, is made all the more resonant by such grouping, the way they speak to each other. The exhibition has also been commemorated by a handsome, scholarly book, Richard Batterham Studio Potter, edited by Tanya Harrod and Sarah Griffin, with rewarding essays and superb photographs by Jon Stokes (V&A Publishing, £30).

Such a retrospective allows critical responses to formulate too, of course – about the way he made monumental versions of domestic forms without much altering them, say, or about the sometimes stretched claims of utility for what clearly are strictly display pieces. But the overwhelming response to the exhibition can only be of gratitude, not only for the creation of such consistent beauty but for the way he made it available for people to incorporate into the fabric of their lives.

I’ve used Batterham’s pots daily for 30-odd years and would be bereft without them. They are a constant kindness in life. Living so closely with them means these simple pieces can shape your sensibility more directly than less accessible fine artworks, I have come to understand.

Batterham, who spent two years at St Ives, was of course a potter in the Anglo-Oriental Leach tradition of the ‘ethical pot’, its value supposedly certified by the quiet rural life of the maker.

This movement, once so dominant, was effectively shredded by the polemical biography of Bernard Leach published by today’s leading ceramicist Edmund de Waal in 1998, exposing Leach’s dodgy orientalism, his surprising ignorance of Japanese, his reliance on assistants for throwing, the windiness of his pronouncements in A Potter’s Book, and so forth.

The vigour of this attack derived partly from the fact that de Waal himself had tried hard for many years to become a Leach-style rural, ethical potter himself, before realising that he simply did not like the heavy murky stoneware he was producing and turning to the exquisite porcelain work for which he is celebrated now.

Perhaps de Waal’s writings have seriously undermined the intellectual foundations of the movement that Batterham emerged from? Perhaps it was almost a fiction? Yet the achievement remains, the work unarguable. It’s particularly poignant thinking about this at the V&A now, where the central cupola of the Ceramics Galleries houses de Waal’s astounding permanent installation ‘Signs & Wonders’, 425 porcelain vessels, arranged in a circle, so high as to be only partially visible, a reflection on the whole history of the collection – while there at the far end of the galleries is displayed for now the tradition that one man working alone made of himself with such singular integrity.

Comments