Given the ingenuity of machine-makers, said Descartes in the 17th century, machines might well be constructed that exactly resemble humans. There would always, however, be ‘a reliable test’ to distinguish them. ‘Even the stupidest man’ is equipped by reason to adapt to ‘all the contingencies of life’, while no machine could ever be made with enough pre-set ‘arrangements’ to be convincingly versatile.

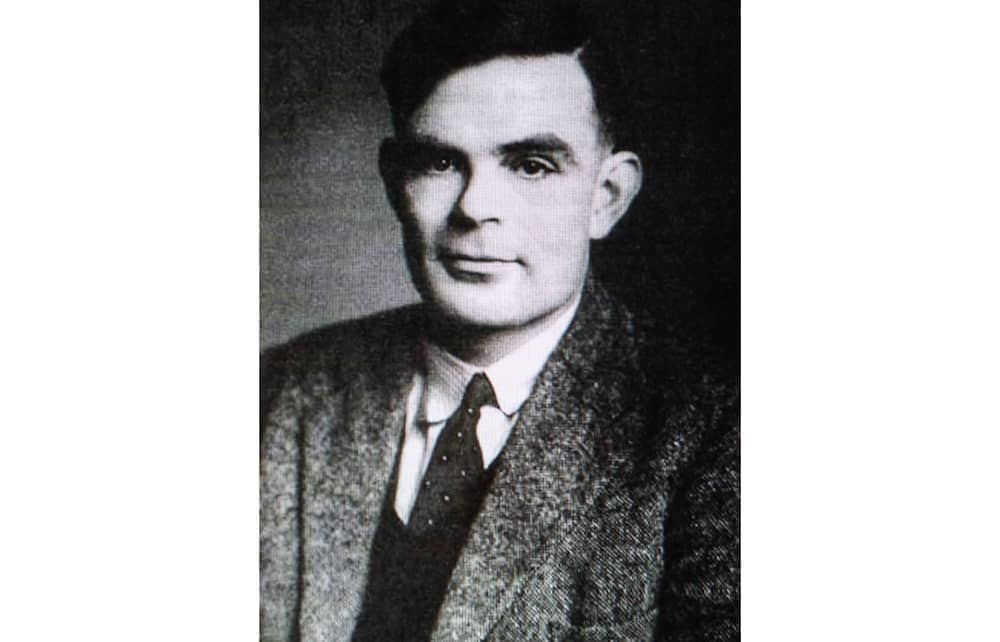

But suppose it could? In 1950 Alan Turing proposed a test remarkably similar to Descartes’s. A computer and a human are asked questions, each being invisible to the questioner, and their respective responses compared. If the computer’s can be mistaken for the human’s, displaying equivalent versatility and apparent spontaneity, then ‘general educated opinion’ would uncontroversially pronounce that machines can think, and appreciate how machine-like the mind is. Turing predicted that this test would be passed ‘by the end of the century’.

But – what is a mind? The science writer Philip Ball pursues this question by presenting a series of answers to it made by recent philosophers. He urges us to explore ‘the space of possible minds’, rather than making the human mind, as pre-Copernican astronomers did the world, central and unique. We estimate other forms of mindedness by how closely these approach our own. We deplore Descartes’s belief that animals are mindless machines, but credit them with feelings and thoughts purely in proportion to how far their behaviour reminds us of ours. ‘Mindedness may be a multi-faceted quality of which human consciousness is just one variety,’ declares Ball. Animals, aliens and machines might possess other versions. Perhaps; but how is mindedness to be discerned?

‘For an entity to have a mind, there must be something it is like to be that entity,’ says Ball, reprising Thomas Nagel famous ‘What is it like to be a bat?’ (1974). But Nagel was reminding philosophers that they were neglecting the subjective character of consciousness, not proposing ‘a definition of mind’. To use quiddity of consciousness as a criterion of mindedness, as Ball does, excludes machines at the outset. It is only ascertainable via introspection (your own or the bat’s, for instance). Nor are ‘internal models of the world’ – another ‘feature of mind’ Ball suggests – open to outside observation. And how could any method at all be used to discern if matter is suffused with mind (panpsychism)? Perhaps (Ball cites Colin McGinn) ‘we can only ever come at [mind] from the inside’. This is rather defeatist so early in the book.

Doesn’t neuroscience ‘go inside’ more objectively, increasingly informing us about mental processes? Ball is at his best when critiquing this popular view. Neural circuits observably ‘light up’ in fMRI scans, he agrees, but sadly do not display accompanying descriptions of what that signifies in each case. Neuroscientists necessarily rely on inferences from the reports of those whose brains are being scanned and on systematic comparisons of these.

It seems hard to dispense with the Cartesian mind/body, subject/object, inner/outer dichotomy. But is the mind, rather than being any sort of entity, nothing other than what it does (functionalists’ solution)? Minds must have evolved ‘to free us from our genes: to allow us actions that are not pre-programmed’, enabling us to adapt, not over aeons but immediately, to new circumstances (which is what ‘free will’ amounts to – Dennett’s point – and it comes in gradations). Brains ‘have different “mind-forming tendencies”’ depending on a creature’s environment. In principle, indeed, brains are not even essential to mindedness, which is whatever it has evolved to be – think of octopuses, birds, ants. Desire, aversion, love and other ‘mental states’ are simply functional roles enacted by a creature’s ‘mind-system’, irrespective of how it is implemented, in particular circumstances.

Ball is wary of extreme, AI functionalism. To satisfy the Turing Test, he complains, is ‘a matter of mere engineering, and irrelevant to the much more profound issue of whether a machine can “think” – which is to say, exhibit mindedness’; the criterion for a computer to count as ‘intelligent’ is ‘merely [for it] to simulate the appearance of intelligence, not to necessarily produce it’. But he misunderstands the Turing Test. ‘Thinking’ and ‘intelligence’ in Turing’s usage (which is now everyone’s) are not mere faute-de-mieux substitutes but the real thing. The boundaries of mind have (exactly as Ball urges) been extended, so that mind-terms which once needed to be used as metaphors, or placed in inverted commas, are treated as literal. Computers are said to ‘learn’, ‘recognise’, ‘communicate’, ‘know’. And minds themselves are declared to be kinds of computer.

Ball gives us an enjoyable ride through different perspectives on the mind but seems unaware of how jarringly incommensurate these are, nor that, by enlarging the parameters of mind, we have simultaneously shrunk them. If we are anthropomorphic in using mind and agent terms for computers, we are mechanomorphic about ourselves, making the mind a matter of processing information.

Comments