I’ve been lucky enough in my working life so far to hold a string of jobs that have allowed me – if not actively encouraged me – to be critical of government. Coming up through Westminster thinktanks in my twenties, I had great fun putting out press releases that tore apart bad public policy. When I had the opportunity to speak to MPs, they’d remind me of the ‘political realities’ that tied their hands and prevented change. In other words, check your policy privilege. Thinktank wonks, commentators and journalists can make all the punchy points they want; they don’t face re-election.

But there was one politician who over the years consistently took the side of the wonks; who thought liberal reforms were possible, so long as one made a compelling case for change. This is how Liz Truss became the darling of the free-market right.

In response to sugar taxes and crackdowns on junk-food adverts, Truss labelled her own government the ‘banny state’. As chief secretary to the Treasury, she lambasted the tax burden hovering near a 50-year high (a low-tax utopia, compared with today). No matter which ministerial job she held, Truss was loud and unshakeable in her commitment to individualism and personal liberty. We free-market types couldn’t get enough.

Often when MPs ascend the government ranks, they quietly drop out of thinktank initiatives designed to bring together free-market politicians. Not Truss. She would stay close to these projects, always turning up to policy paper launches and drinks receptions to give speeches. She was good at garnering media attention. When the Institute of Economic Affairs launched a social freedoms paper in 2019, with the essay ‘On the Nanny State’ penned by Truss, Krispy Kreme doughnuts were piled high on tables as a statement against anti-sugar policies – and for selfies.

When Truss was pushed by Rishi Sunak in the second leadership debate to explain her journey to conservatism, she said her ‘political journey’ had been shaped by her schooling. In 2019 on the IEA podcast, she told me something different: ‘The reason that I became a Conservative,’ she said, ‘is I hate being told what to do.’ I prefer this answer. It neatly sums up Truss as a politician. Her campaign promises to ‘challenge the orthodoxy’, slash tax and go for growth are not some new bid to win over the right of the party, they are long-held and well-considered beliefs that stem from one principle: that the state should not have such a grip on people’s everyday lives.

Liz Truss’s increasingly cosy relationship with borrowing and debt doesn’t sit right with me

Lots of free-marketeers are excited about the prospect of Prime Minister Truss and the start of a lower-tax era. After all, we’ve been waiting for years for someone to enter No. 10 who sees the tax burden as the menace it is. Yet I can’t shake the gnawing feeling when Truss goes head-to-head with Sunak on tax that something isn’t right. There’s a piece missing from Trussonomics today that was fundamental to her old economic agenda. To cut tax sustainably, you also have to slash the size of the state. But Truss has dropped spending cuts as a priority in her bid to be leader.

She has even followed Boris Johnson’s example in claiming that austerity after the financial crash was a mistake. Arguments about fiscal responsibility are being left to Sunak, who, having spent hundreds of billions to get through the pandemic, is now calling time on printing money. Meanwhile Truss seems swept up by the spending spree. She’s proposing deficit-financed tax cuts, which she insists will spur on growth.

Plenty of the economists I respect have given their sign-off to Trussonomics – and they may well be right that there’s more wriggle room in the public finances to cut tax than Sunak suggests. But Truss’s increasingly cosy relationship with borrowing and debt still doesn’t sit right with me. She says Covid debt should be treated differently; that the National Insurance hike was the wrong approach to tackling it and she made her feelings known in cabinet. What’s left out of this version of events is that the NI rise wasn’t really for Covid, it was to cover social care bills – including the bills of the affluent. Truss privately agreed with Johnson’s original plan to throw this hefty day-to-day health spending on to the deficit.

There are also plenty of unanswered questions about how Truss plans to get inflation under control. As Britain nears double-digit inflation, Truss is right to point out failures in monetary policy, to question the Bank of England’s remit and to challenge the orthodoxy that its independence from government makes it immune to any criticism. But none of this actually gives her control over interest rates. And if the Bank were to raise rates under her leadership, she has so far shown unwillingness to acknowledge what that means for mortgage repayments or credit-card debt.

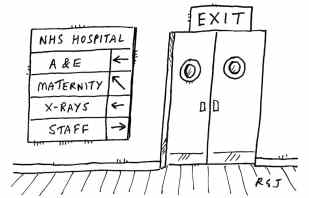

I’m not an outright pessimist – at least not when it comes to the economy. ‘Going for growth’, as Truss says she wants to do, can replace the need for major spending cuts or tax hikes. But it requires acknowledging the abysmal financial state we’re in and then putting forward plans to shake up the public sector. Despite vying for the title of the heir to Margaret Thatcher, neither candidate is discussing how she overhauled and reformed the public sector. Today’s expensive failures, like the National Health Service, are not even up for discussion.

According to the Office for Budget Responsibility, our current spending path will take debt to 320 per cent of GDP in 50 years’ time. We couldn’t afford all our spending commitments before the pandemic, and we certainly can’t now. I used to rely on Truss as one of the few brave MPs who would make this case. ‘I think there’s an issue of politicians over a number of years claiming they can deliver everything,’ she told me in that same podcast. ‘And that is just not true.’ It’s the kind of thing Sunak is saying nowadays, which Truss might call ‘Project Fear’.

Comments